- Introduction: Community Action Model

The Community Action Model (CAM) is a five-step framework for building the capacity of community-based organizations to address health inequities through policy, systems, and environmental change. The CAM brings together community residents, community-based organizations, and the City and County of San Francisco’s Tobacco-Free Project to design and implement community-driven campaigns. The health disparities that exist between, on the one hand, low-income communities and communities of color, and, on the other, more affluent communities, are well documented. There are higher smoking rates, higher concentrations of outlets that sell tobacco, and more advertising and promotions of smoking in low-income communities and communities of color. Recognizing the need to bring community members into the conversation to solve these health inequities, the SFDPH Tobacco-Free Project has utilized the CAM framework to fund organizations working on tobacco-control issues since 1996. This case study provides a brief description of San Francisco’s use of the CAM and documents lessons learned and best practices for other public-health agencies implementing community-capacity-building efforts.

Youth Leadership Institute TURF CAM Advocates 2008

- Community Action Model: Roles of Partners and 5 Steps

The SFDPH Tobacco-Free Project has used the CAM framework to provide funding and technical assistance to community-based organizations since 1996. Rooted in Paulo Freire’s popular education theory, the CAM was developed by San Francisco’s health educators in the early 1990s.[1] Instead of focusing on changing the individual behaviors of community members, the CAM builds the capacity of community-based organizations to upend the systemic forces that create health inequities. The underlying theory of the CAM is that community members become effective agents of change when they are engaged in the development of solutions that improve the conditions that oppress their communities. The CAM’s five-step framework allows community-based organizations to intentionally engage, lead, and train community members in these systems-change objectives.

Partnering with Community-Based Organizations and Residents

To implement this model, the Tobacco-Free Project uses a competitive request-for-applications (RFA) process to solicit applications from local community-based organizations that are interested in working on tobacco-control campaigns that eliminate health inequities in low-income communities and communities of color. The Tobacco-Free Project selects a cohort of organizations to receive a two-year grant of approximately $175,000. The amount of funding available to organizations has varied over the years on the basis of the availability of resources and the budget of the Tobacco-Free Project. With the funding received, organizations appoint a project coordinator and recruit up to eight community residents to participate in the project.

The Role of the Tobacco-Free Project

The Tobacco-Free Project plays the role of funder, convener, and trainer. During the two-year cycle, the Tobacco-Free Project staff work closely with the project coordinators from the funded organizations to implement the five-step model. Funded organizations and advocates identify the issue that resonates most with their community. While organizations work with their own teams on the selected community issue, San Francisco’s program structure allows the organizations to move through the five steps as a cohort in a learning community setting. The Tobacco-Free Project provides ongoing training and technical assistance to the project coordinator and advocates throughout the two-year cycle to ensure that they are able to conduct data collection, analyze data, and identify and implement a realistic action or activity that has the potential for social change.

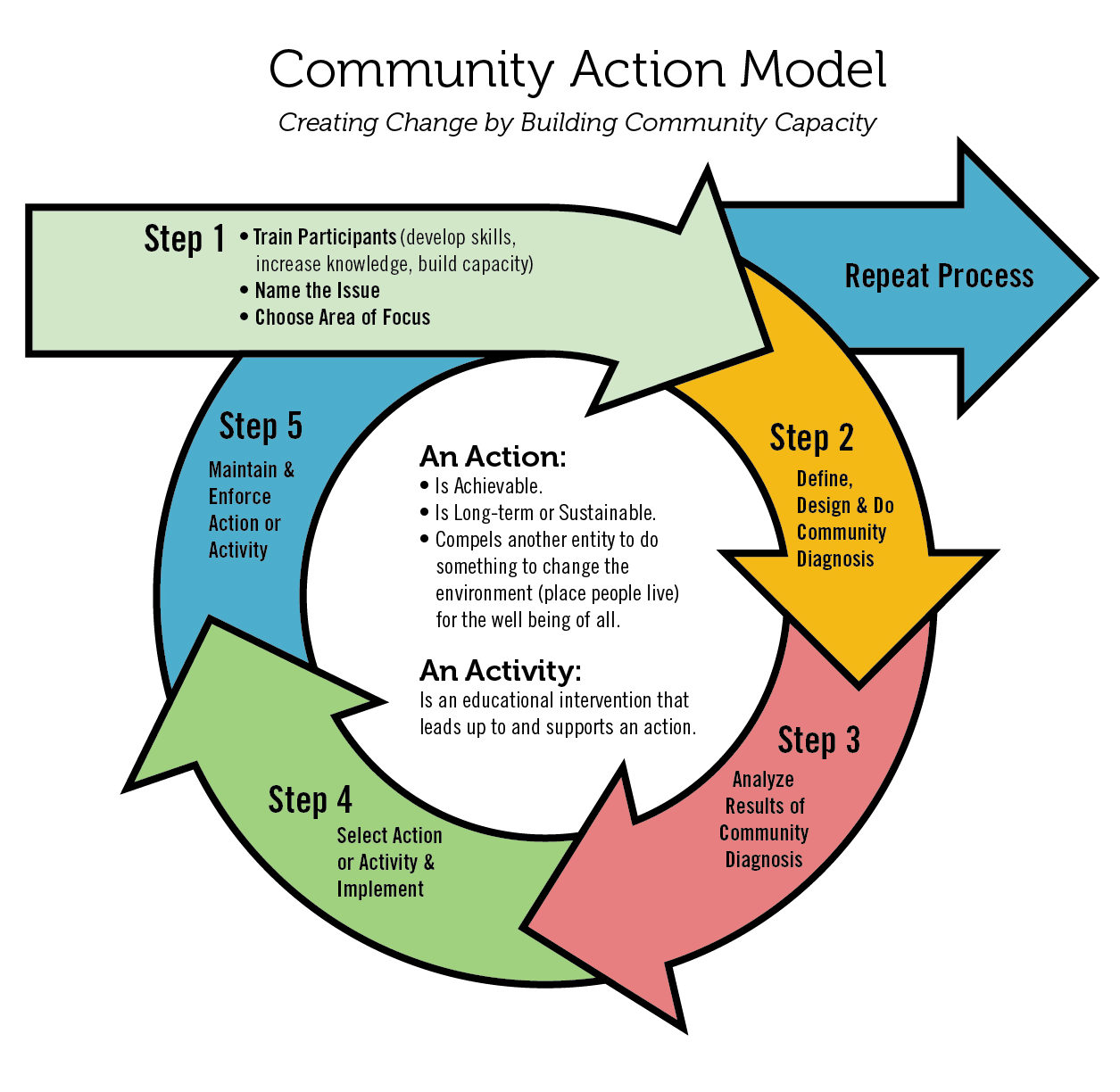

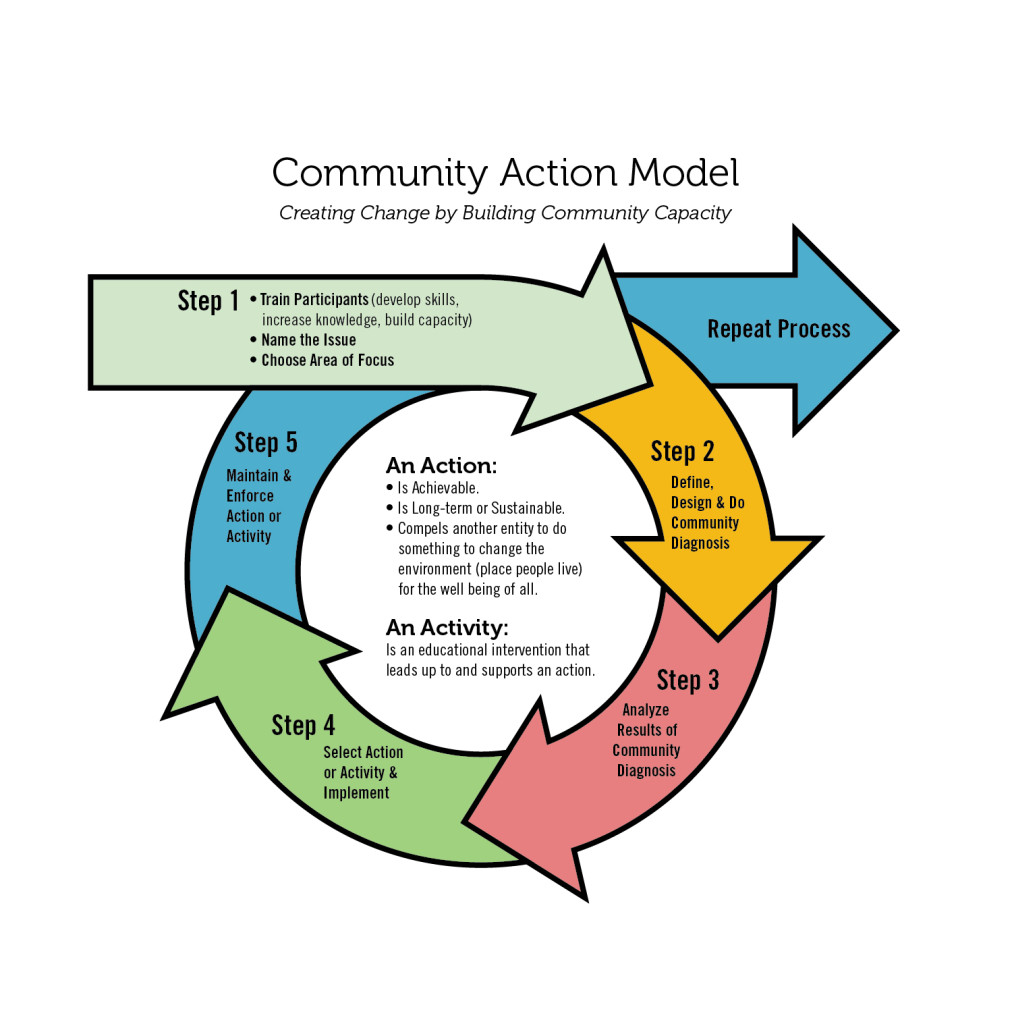

The Five Steps in the Community Action Model

Each of the five steps builds the capacity of the organizations and advocates to understand a critical step in systems-change work. A curriculum and tool kit in three languages accompanies each of the steps.[2] Capacity building through training is ongoing and tailored to the skills needed to complete each step of the CAM process.

Step1: Train. First, the project coordinator and advocates are provided with education and training about the history of the transnational tobacco industry; tobacco control, public health and health inequities; and policy, systems, and environment change. During this phase, each CAM group must select a specific community issue that they want to address, such as smoke-free housing or tobacco advertising. Advocates are encouraged to think creatively about tobacco control and to integrate related issues that have deep meaning in their community, such as housing rights, food security, or other equity issues.

Step 2: Diagnose. During the second step, advocates conduct a community diagnosis to assess the strengths and needs of their community. The diagnosis phase may include qualitative and quantitative research methods like focus groups with neighbors, interviews with key policymakers or stakeholders, public-opinion surveys, community-mapping projects, counting/observations, and other methodologies.

Step 3: Analyze. The third step includes analyzing the results of the diagnosis to identify key findings that help narrow the focus of their selected issue and to identify a menu of possible actions or activities that could address the issue. Learning to message the issue and share these key findings is a pivotal next step toward creating change.

Step 4: Implement. The fourth step is implementing the selected action, such as advocating for a city ordinance, revising regulations, working with a private business to change its practices, etc. Advocates are encouraged to define an action that meets three criteria—it is achievable; it is long term / sustainable; and it compels another entity to do something to change the environment for the well-being of all. These criteria are critical differentiators for the CAM because it requires advocates to go beyond an educational intervention in identifying an outcome that changes the policies, systems, and environments in which their community lives.

Step 5: Enforce. The final step is to enforce the action to ensure that the intended systems change takes hold.

Through each step, community advocates are the foot soldiers; project coordinators are the organizers; and the public-agency staff (i.e., the Tobacco-Free Project staff) are the coaches. The steps allow each of these partners to play unique but complementary roles in supporting community health initiatives. For example, in 2009, the Youth Leadership Institute’s community diagnosis revealed that there was a higher concentration of retail stores that sold tobacco in low-income neighborhoods compared to high-income neighborhoods—meaning higher levels of access to tobacco and increased exposure to harmful advertising in lower income communities. Instead of working with individual retail stores to stop selling tobacco, the CAM group developed an innovative ordinance that would cap the number of tobacco-retailer licenses in each jurisdiction in San Francisco, thereby attempting to create a more equitable retail environment in all neighborhoods. The San Francisco Tobacco Retail Density Policy was eventually adopted because of the support and strategy of the CAM project, and the CAM team has partnered with the local enforcement agency to ensure that stores that lost their tobacco retail license are no longer selling tobacco.

For more details on the San Francisco Tobacco Retail Density Policy and other specific projects that have utilized the CAM in San Francisco, visit the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project website.

[1]. For more information about the CAM, please see the list of articles and resources at the end of this case study.

[2]. CAM tool kits for community agencies can be found here: http://sftobaccofree.org/actions/.

- Best Practices for Community Capacity Building:

Public health departments achieve greater success and enjoy more legitimacy when they partner with impacted communities and support upstream efforts to impact the social determinants of community health. As a result, public health departments are moving away from the role of funding only direct-service providers toward building community capacity to advance policy, systems, and environmental change to address health equity and to be responsive to communities. Public health departments in city or county governments can benefit from frameworks that support community-driven solutions to public-health goals.

While community partners often have deep expertise about the needs and strengths of their communities, they may not have the skill set or capacity to move beyond the community asset and needs assessment phase to develop actions or solutions that can create systems change. As public health agencies decentralize their work by funding community partners, they often struggle with finding a good framework for supporting community-driven systems-change campaigns that are realistic, actionable, and aligned with the goals and funding streams of the public health agency.

The CAM bridges this gap by providing a strategy that draws on the strengths of both the community partners and the public health agency. The result is a public-agency-supported, community-driven effort to define community strengths and needs, and promote solutions that are actionable and grounded in best practices. By seeding community participation, the goal of the CAM is for the community to acquire the skills to go beyond simply being engaged to driving the process in partnership with the public health agency. Informed by over 20 years of experience implementing this model in San Francisco, the CAM is a best-practice framework for partnership between public-agency and community partners. This section details the lessons learned and considerations for other public agencies interested in implementing a community-capacity-building model.

- Lessons Learned about Community Capacity Building:

In a community-capacity-building framework, public agencies must develop greater comfort with allowing the community partner to define the action agenda and implement the campaign.

This model upends the traditional role of the public agency as an external funder and judge of the value of a funded community project. The CAM expands the role of the public agency beyond that of a traditional funder toward that of a partner and capacity builder. Similarly, instead of simply being the receiver of funds, community partners share their community expertise while engaging in technical assistance and insight that builds their skills and insider knowledge related to systems change.

In its role as “expert” on policy and systems, the public agency can support community partners in selecting CAM actions that are realistic, achievable, within the purview of local control, and likely to yield the desired outcome. However, the public agency must create space for the community partner’s expertise in understanding the lived experiences and behaviors, concerns, and preferences of residents to drive the community campaign. This means stepping back and being comfortable with the CAM actions being defined by the community’s interests and diagnosis as opposed to the public-health-agency’s interests. The CAM requires a mutually respectful relationship between the public agency and community partner, with a structured and consistent partnership throughout the two-year cycle.

CAM Advocate Skills: - Social determinants of health

- Health Equity

- Qualitative Research: Key Informant interviews, focus groups, photovoice

- Quantitative Research: surveys, mapping

- Literature Review

- Message development

- Media advocacy

- Community Organizing

- Public speaking

- Policy Development

Community capacity-building requires a focused investment over multiple years.

Policy change takes time and requires multiyear investments and strong community-based partners that are able to dedicate the resources to focus on a single issue or action for several years. A CAM grant is awarded for two years because it is expected that the training, diagnosis, analysis, action, and implementation related to a single issue takes that long, and sometimes even longer. This is different from traditional grants, which often provide general operating support for the nonprofit, which might mean that a nonprofit is able to work on several different projects or actions at the same time. A public agency plays an important role in building community-partner tolerance for the slow pace of policy work.

In addition, turnover may occur among advocates and project coordinators over the two-year period—a common challenge in nonprofit environments that must be considered when making these types of investments. Public-agency staff should plan to provide support and leadership in staff transitions so that the work done is not wholly dependent on one person holding it together. The consistent training and regular communication between the public agency and the community-based organizations and advocates ensure that these transitions are as seamless as possible. As a result, even if participants do not work on the CAM over the entire two years, the project coordinators and advocates should still be able to walk away with knowledge and skills that they did not have before participating in the project.

Community capacity-building should provide a cohort experience among the funded organizations, coupled with individual support.

The CAM’s intended outcomes are twofold: to create social change through community participation and to deepen the skills and knowledge of the community so that they may continue to apply the lessons learned from the CAM in affecting social change after the grant ends. As opposed to traditional grants, a CAM grant requires regular and consistent communication between the public-agency funder and the organizations participating in the cohort. The public-agency funder needs to make clear the requirements for staff participation and other organizational resources that might be needed in order to receive this grant.

Under the CAM model, the funder takes on a greater role in supporting the organization’s success through individualized support that is tailored to the strengths and needs of the organization and its project. When the support needed is not within the expertise of the public agency, the funder should be prepared to broker access to external trainers and technical-assistance providers that support each organization as needs arise. In addition, creating a cohort experience allows the organizations to learn from each other and share resources that might be limited at each of their organizations. The CAM-cohort experience, coupled with individual support, ensures that organizations move through each phase required to complete a CAM action while at the same time providing organizations the flexibility to dig deeper into each phase if they want to or need to.

A timeline for CAM projects The success of a community capacity-building project should be defined by the increased capacity of the community partners.

The success of the project should not be whether the intended action was achieved. While affecting policy, systems, and environmental change is one of the goals of each project, as a funder the public agency should evaluate success on the basis of the extent to which the funded group acquired skills and stayed on track to meet project benchmarks. To achieve this, the public agency needs to set up a structured set of benchmarks, timelines, tools, training, and other technical assistance to shepherd the funded group through the process so they meet the project deliverables. The funded group needs to define the content of the CAM project so that the issue they have chosen has deep meaning to them and therefore is an issue that they are fully invested in achieving. The action is dependent on many outside forces and political pressures that may make the action unsuitable for that point of time. In San Francisco, many CAM projects that did not successfully achieve their action during the first cycle were able to continue to collect data, ideate, and garner support to ultimately achieve success in a subsequent cycle of CAM grant funding. The focus on community capacity building as the ultimate success marker of a grant engenders support and deepens participation from the community-based organizations and advocates.

Check out the website for the CAM timeline, curriculum, and other tools that can be utilized by other funders interested in implementing the CAM.

- Required Resources for Public Agencies Implementing the CAM :

Compared to a traditional contracting relationship, the CAM requires a greater investment of resources from the public-agency funder, community partners, and other external resources. The public agency, such as a local health department, needs to align resources that respond to the needs, strengths, and preferences of community partners in the CAM cohort. The CAM requires a predetermined structure that includes regular individual and cohort meetings, dedicated staff time, and project timelines and benchmarks. This table describes the conditions and resources that must be in place to successfully support organizations funded by the CAM.

Public Agency Resources for the CAM Dedicated Staff Coordinator The CAM requires that the public-agency funder, e.g., the local health department, have at least one full-time staff person who is coordinating and managing community partners and engaging other agency or external resources that can support the CAM partners. This is a resource investment for a public-agency funder. At least 75% of the time of a full-time equivalent staff person should be dedicated to overall project management. Staff Coaches Each organization is assigned a project coach from among the staff of the public-agency funder. These coaches have monthly or bimonthly check-in meetings with their CAM partner. The purpose of this relationship is to provide additional education about the CAM steps, to manage the CAM partner’s performance regarding their work plan and deliverables, to be a thought partner on project strategy and actions, to serve as a bridge to city staff or stakeholders who can help them with their project, and to broker resources to other technical-assistance providers who can build the capacity of the organization. For example, an organization might share that their youth advocates do not feel confident about the public-opinion survey tool that they developed, and the coach may connect them to a survey methodologist who can meet with the advocates to help them improve their tool. Organizations have different levels of readiness—meaning that some organizations need a greater level of support than others. Coaches should work on assessing each organization’s readiness with the project, and broker resources accordingly. Performance Management The CAM partners need to have a concrete work plan with deliverables and benchmarks. At the beginning of each of the five steps, the community partner develops a workplan for that phase with the assistance and guidance of their staff coach. The workplan activities and benchmarks must reflect the activities that the community advocates want to complete in order to meet the overall objective of that step in the CAM cycle. At the end of each step, the CAM partner provides a summary report of what was achieved during that step. For example, at the beginning of step 2, a partner will develop a Community Diagnosis Plan, which may include key informant interviews, surveys, focus groups, research on existing policies, or other methodologies that identify community assets and needs. The coach will refine this plan to ensure that it is realistic and that the target populations for each methodology are appropriate. The coach will also use that plan to broker resources and trainers who can help them complete that step. That step will be considered complete when all the activities in the work plan are completed and summarized in a report. The summary will then be used to build out the work plan for the next phase in the CAM cycle. While some organizations take longer than others to complete a step in the CAM cycle, they are generally required to ensure that their work plan for each step is completed in the same time frame. This allows for the cohort experience to flourish and reduces the risk of a community partner’s not being able to complete the entire CAM cycle.

Funding Source Public agencies face the challenge of promoting a community-capacity-building project in the context of funding sources and restrictions. Funding sources often create conditions that lead public agencies to work on projects in silos. The CAM is a framework that can be applied to any range of public health or other issues. Restricted funds may be able to be used for these projects if the topic or issue selected is related to the purpose of the funding stream. The scope of activities and issues that community partners can implement should be included in the RFA and contracting process. In San Francisco, the Tobacco-Free Project has engaged organizations to work on actions that reduce access and exposure to tobacco. However, there are few community partners that have an explicit organizational tobacco-control focus. Many partners are youth-development organizations or public health service organizations. The CAM staff must work closely with organizations to integrate the issues that are of greatest community concern with the tobacco-control mission of the associated funding source. RFA Process Public-agency funders need to administer an RFA process to solicit applications from organizations that are interested in participating in the CAM. Because impacted communities are disproportionately low-income and communities of color, the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project is intentional in its recruitment of organizations that represent diverse communities in San Francisco. Public-agency staff use tools that assess each organization’s cultural competency; fiscal, administrative, and staffing capacity; and experience with community organizing and youth or adult volunteer recruitment. Learning Community/ Cohort The project coordinators from each CAM partner are convened on a monthly basis in a learning community setting. Led by public-agency staff, these meetings aim to deliver group trainings, review each organization’s progress on their work plan, discuss common challenges and innovations, identify resources that can help one or more partners, and network and build relationships between all the partners. Training is provided to project coordinators throughout each step of the CAM model in a train-the-trainer format. The project coordinators adapt these trainings to the competencies and preferences of their advocates to build their capacity. The learning objectives for project coordinators include developing data-collection methodologies, data analysis, a model policy development, testimony in front of decision-making bodies, media advocacy, and strategic communications. Training and Support for Advocates The CAM project coordinators are required to recruit community residents to participate as advocates in the CAM project. The project coordinators meet with their advocates on a weekly or biweekly basis to implement the activities in the work plan. The project coordinators also train advocates and build their capacity to do systems-change work using the tools provided in the learning community setting. The CAM encourages partners to structure the advocate relationship as a paid internship, with advocates receiving between $80 and $200 a month to participate in regular advocate meetings and ad-hoc trainings, and to conduct the activities included in the work plan. The learning objectives for advocates include data management, messaging, public speaking, interviewing, policy-development skills, and knowledge of tobacco industries, tobacco policy, health disparities, and social justice. - Conditions for Successful Partnership with Community Based Organization:

The CAM uses a tiered approach to capacity building that touches the public agency, community partner, and community advocates. There are four conditions that determine whether a CAM project is successful in building community capacity for systems change: 1) the reputation of the CAM partner organization; 2) the qualifications of the project coordinator; 3) the organization’s relationship with a coach from the public-agency funder; and 4) the effective participation and engagement of resident-advocates.

The community partner—represented by the project coordinator—is a critical bridge between the coaching role of the public agency and the implementing role of the community advocates. Community partners need to bring trusted relationships with diverse community members and deep experience with community organizing. The leadership within the partnership must be committed to the CAM project and understand the staff time and resources needed to implement this project.

A successful project coordinator has knowledge and expertise of the community, the ability to work with a team of advocates in a training/coach role, and the ability to receive training on policy work. A project coordinator must be an organized person who can shepherd advocates through a predefined process. The staff person who serves as the project coordinator must dedicate approximately 75% of their time to the project. They must also be able to communicate with multiple audiences, including communicating with public-agency staff regarding work plans and budgets; policymakers and stakeholders regarding their CAM project; and community members regarding the CAM process and the purpose of systems-change projects.

Finally, the staff coach from the public agency must develop a positive, cooperative relationship with the community partner. The coach plays an integral role in supporting the project coordinator and brokering resources that can ensure that the organization and its advocates gain and share skills related to systems change. Coaches should be matched to the organization depending on their knowledge of the topic that the organization wants to work on and their experience with the organization’s mission, values, and guiding frameworks (for example, youth development, community organizing, or other values).

- CAM Profile: Tonya Williams

Tonya has served as the chair of the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition since 2010. When she began using the CAM, she was the executive director of the Girls After School Academy, where she served for over 11 years. She currently works as an associate at Crawbren & Associates LLC.

Tonya has served as the chair of the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition since 2010. When she began using the CAM, she was the executive director of the Girls After School Academy, where she served for over 11 years. She currently works as an associate at Crawbren & Associates LLC.What was the impact of the CAM?

“Working with the CAM model opens the hearts and minds of everyone who is involved with it, from the youth to the project coordinators to everyone they interact with. It allows people living in impoverished areas to look at their community through a new lens. People often think, ‘How does tobacco matter to my life? I’m hungry. I need a new pair of shoes.’ But CAM taught them to think about the impact of tobacco on their communities, to better understand how tobacco companies intentionally target their communities, and to use their power to protect their neighbors, loved ones, and themselves.”“The highlight of working on CAM is always the impact you see on the health advocates. In my first project working on smoke-free public housing, I worked with girls who were from the most impoverished area in San Francisco—and no one ever expected them to care about or investigate these issues. Everyone’s expectations—including their own—were low for these girls. Where so many of their peers were not finishing high school, so many of the girls who participated in the CAM project were so inspired that they excelled in school and completed college. CAM instilled in them the ability to care about themselves and their ability to influence the community. The steps for CAM are not just about a public-health model; CAM instills lifelong skills like life mapping or planning, communication skills, teamwork, and camaraderie. CAM taught these girls to ask the right questions and to go one step at a time until they find a solution that works.”

CAM Projects (2002–2012)

Smoke-free public housing

The San Francisco Housing Authority adopted a 100%-smoke-free-building policy for all 6,543 public-housing units in the city.Rejecting tobacco funding

Four local African American cultural organizations adopted policies that rejected funding from tobacco companies or their subsidiaries.

Storefront advertising

A city policy that reduced the percentage of store windows dedicated to alcohol advertisement

- CAM Profile : Mele Lau-Smith

Mele began working for the Tobacco-Free Project in 1991. She collaborated on the development of the CAM and worked with the model for 15 years. She continues to use the CAM in her current position as the Executive Director of the Office of Community Schools and Family Partnerships at San Francisco Unified School District.

Mele began working for the Tobacco-Free Project in 1991. She collaborated on the development of the CAM and worked with the model for 15 years. She continues to use the CAM in her current position as the Executive Director of the Office of Community Schools and Family Partnerships at San Francisco Unified School District.What was the process of developing the CAM?

“When we began our work, people thought about tobacco control in terms of individual-behavior change, and all of the interventions were focused on getting people to quit smoking. We came together to look at community organizing and policy change as a way to change the environment to prevent young people from starting to smoke in the first place… The CAM focuses on recognizing and valuing the knowledge and skills of those most impacted by the predatory nature of tobacco companies and provides them with a framework to identify tobacco-control policies that can transform health and lives…Every time we implemented the model, we learned something new. It took about 10 years of iteration for the model to develop into what it is now.”

Why do we need the CAM?

“The CAM supports the whole idea of public health from a social-justice perspective, of trying to change the power structures that create the haves and the have-nots. If you really get down to it, the practice of public health done well is about creating equity. When you start with a model that has this at its basis, those most impacted by the political, cultural, and socioeconomic

- CAM Profile: Angel Rodriguez

Angel served as a youth advocate in the Bay Area Community Resources (BACR) CAM project in 2015. In 2016, Angel was hired by BACR as the project coordinator for the same CAM project.

Angel served as a youth advocate in the Bay Area Community Resources (BACR) CAM project in 2015. In 2016, Angel was hired by BACR as the project coordinator for the same CAM project.What is it like working with the CAM model?

“CAM is like our car—it helps us get places. Without it, we wouldn’t know where we were going. Each step is followed by a different action to complete the ultimate goal. As an advocate, when I first learned about the work we would be doing, it was overwhelming. ‘We’re supposed to do what? In how long?’ It’s a lot, but if you take the time to digest each step and how it leads to the next step, you see that it can be done. It’s the perfect model. It’s so organized. You can’t really fail.”

What is the best part of working with CAM?

“Coming into this, I thought about people smoking as an independent decision. If it’s hurting them, they’re just hurting themselves. I didn’t think about how it was affecting others or about the unwanted consequences of smoking inside. When we started talking to other organizations and people, we saw that this is a bigger community problem that a lot of people care about.”

What have you learned while working with the CAM?

“Creating a policy is a really long process. It’s not just one meeting with your Supervisor. It’s a process that you have to prepare for and think about the outcome. The CAM model helps you look at the bigger picture. It helps you meet people and organizations that you wouldn’t have connected to. It shows you how important building relationships is.”

CAM projects

(2015–present)Smoke-free multi-unit housing

Currently advocating for landlords to voluntarily adopt smoke-free policies for multi-unit housing complexes in San Francisco.

Tobacco price increase

Currently developing a policy to increase the minimum price of tobacco products in San Francisco. - CAM Profile: Rosalyn Moya

Rosalyn was a CAM project coordinator in 2012 when she worked for Breathe California, a member of the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition. She currently works as a project director at Bay Area Community Resources.

Rosalyn was a CAM project coordinator in 2012 when she worked for Breathe California, a member of the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition. She currently works as a project director at Bay Area Community Resources.What was the impact of the CAM?

“When we gathered data, we got out into the community, talked to the community, and understood people’s arguments. This process gave us data and prepared us to talk to other people in the community about the work we were doing.”

“The CAM model was a good and comfortable introduction to the advocates on how to get a policy passed. The advocates already had a background in public health but had never worked in policy. The CAM model helped them understand and be comfortable with policy, the steps to get data, and how to get a policy passed.”

What did you learn from working with the CAM?

“I learned a lot about policy. I worked in tobacco for a long time, but that was my first time working in policy. While I was learning policy in the CAM model, I was also teaching it. But I had a lot of guidance from my supervisor, DPH, and the structure of the model.”

“The CAM model was clear in terms of the steps that you need to take and the order to do it in. It didn’t feel overwhelming to have to do a bunch of things at the same time. It made the process of getting a policy passed very easy to understand.”

CAM Project (2012)

Smoke-free street events in San Francisco

A San Francisco policy that made all street events in San Francisco smoke-free.

- Conclusion:

For 20 years, the CAM has been used by the San Francisco Department of Public Health to build community capacity to participate in policy, systems, and environmental changes. The CAM is a framework that can be used by public-agency funders who are pivoting away from funding individual-behavior-change efforts and moving toward systems-change efforts that improve community health. This case study documents lessons learned and best practices for other public-health agencies considering implementing community-capacity-building efforts.

Resources

CAM Project Case Studies

http://sftobaccofree.org/case-studies

CAM Tool Kits for Community Partners (available online in English, Spanish and Chinese) http://sftobaccofree.org/actions/

CAM Curriculum for Public-Agency Funders (available online in English, Spanish and Chinese)

https://www.sfdph.org/dph/comupg/oprograms/CHPP/CAM/default.asp

“Community Action Model: A Community-Driven Model Designed to Address Disparities in Health” in the American Journal of Public Health, April 2005

http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.2004.047704

Evaluation of CAM Projects in San Francisco, 2013

https://sanfranciscotobaccofreeproject.org/case-studies/increasing-cultural-competence/

For additional questions, please contact Derek Smith, Director of the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project, at [email protected].

- Appendix: CAM Projects 1996-2016

The table below lists all the CAM projects and associated actions funded by the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project from 1996 to 2016.

Organization Advocates Community Action 1995–1996 LGBT Smoke-Free Queers LGBT Adults Castro Eleven merchants voluntarily removed tobacco ads San Francisco African American Tobacco-Free Project (SFAATFP) African American Adults Bayview and Western Addition Worked with merchants to increase compliance with sign laws Boys & Girls Club of San Francisco: Columbia Park Clubhouse (CPB&GC) Youth Mission Merchants reduced tobacco ads and initiated street cleaning Chinese Progressive Association (CPA) API Youth Chinatown Put in place an SFUSD policy that banned tobacco promotional items Escuela De Promotores Latino Adults Mission Reduced tobacco ads and promoted smoke-free homes 1996–1998 CPB&GC Youth Citywide Worked with The San Francisco Planning Department to support compliance of tobacco retail stores with local tobacco control laws CPA API Youth Citywide Removed a tobacco-ad billboard SFAATFP/Polaris Youth Citywide Removed a tobacco-ad billboard Mission Housing Development Corporation (MHDC) Youth Mission Sent a letter to the California legislature supporting a law that would remove tobacco billboards within 1,000 feet of schools San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners (SLUG) Youth Bayview-Hunters Point Integrated tobacco topics into the Environmental Justice Resource Center South of Market Center (SOMC) Youth Citywide The San Francisco Recreation & Parks Commission adopted a policy to prohibit smoking in outdoor playground areas Booker T. Washington School (BTW) Youth National Filed a complaint with the Federal Trade Commission to enforce rules on the labeling of tobacco products; supported local enforcement efforts of sales to minors regulations for tobacco retailers 1998–1999 BTW Youth National Commented on federal warning requirements for cigars, single cigars, and Black & Mild cigars. Filed a complaint with US Customs and Border Protection (Sec 307 of the Trade Act) CPA Youth Supported efforts to allocate $1 million of Master Settlement Agreement funds to tobacco control, leading to Prop A Mission Agenda Adults Mission Advocated for policy requiring any single-resident-occupancy hotel receiving city funds to meet minimum requirements for decent living conditions, including fire-safety measures SLUG Youth Bayview- Hunters Point Limited tobacco ads in areas where youth congregate SFAATFP (with BTW) Youth National Filed a complaint with US Customs and Border Protection regarding Sec 307 of the Trade Act. Supported a policy requiring police training for sales to minors MHDC Youth Schools The Commercial-Free Schools Act was adopted by the SFUSD, which included removing tobacco-industry-subsidized food products from schools Mission Agenda and Homeless Prenatal Program Adults SROs Advocated for policy requiring any hotel receiving city funds to meet the minimum requirements for decent living conditions, including fire-safety measures CPB&GC Youth Citywide Advocated to strengthen or add outdoor-smoke-free policies at Boys & Girls Clubs and YMCAs 1999–2001 BTW Youth Citywide Advocated for policy on smoke-free common areas in multi-unit housing CPA Youth National US delegation to adapt language around tobacco control Horizons Unlimited Youth Mission The board of directors at Horizons Unlimited adopted a policy to not purchase tobacco-subsidiary food products Mission Agenda Adults SROs n/a MHDC Youth Citywide Enforced the Commercial-Free Schools Act SFAATFP Adults Citywide Forty places of worship adopted a policy to not accept tobacco-industry funds SLUG / Literacy for Environmental Justice (LEJ) Adults Citywide Adopted a policy banning tobacco-subsidiary food products at PAC (community cultural events) 2001-2003 LEJ Youth Citywide Advocated for Good Neighbor Policy for healthy retail stores Girls After School Academy (GASA) Youth Sunnydale Advocated for smoke-free multi-unit housing in Sunnydale public housing SFAATFP Adults Citywide Worked with local African American cultural organizations to adopt policies that refused funding from tobacco companies and subsidiaries MHDC Youth Mission Maria Alicia Apartments adopted a voluntary smoke-free multi-unit housing policy American Lung Association (ALA)—San Francisco and Marin Adults Citywide Four housing complexes adopted a smoke-free policy Latino Issue Forum Youth College Campuses Two campuses adopted divestment from tobacco companies and banned tobacco sales and advertising Youth Stewardship Program (YSP) Adults Citywide Advocated for a policy for smoke-free entrances to buildings 2004–2006 LEJ / Youth Leadership Institute (YLI) Latino Youth Citywide Advocated for the Board of Supervisors to charge tobacco manufacturers a mitigation fee for the harm their product causes People Organized to Win Employment Rights (POWER) African American Adults Citywide Advocated to amend US policies to require graphic warning labels on tobacco packages using research on policies in other countries PODER/CPA Latino and Asian Youth Citywide The San Francisco Health Commission adopted a resolution incorporating community and geographic indicators into evaluation criteria for tobacco-control funding to ensure that monies go to those communities most vulnerable to health disparities resulting from tobacco use Thad Brown Boys Academy African American Youth Ocean View Advocated for smoke-free transit-stop law in San Francisco GASA African American Youth Sunnydale Advocated for banning tobacco-industry sponsorships of African American organizations Project RIDE Asian Youth Asian American Successfully advocated for the adoption of policies to not accept tobacco sponsorship funds by Asian American events / car shows Queers Mobilized Against Tobacco Sponsorship / ALA Adults LGBT Successfully advocated for the adoption of policies to not accept tobacco-sponsorship funds by LGBT events 2007–2010 Breathe California Golden Gate (BCGG) Adults LGBT Ten LGBT-serving groups and two LGBT groups adopted policies to not accept sponsorships from tobacco companies Dolores Street Community Services Adults SROs Established the “311” SRO program to enable tenants to file complaints with city departments Sunset Russian Russian Adults Sunset Promoted voluntary smoke-free housing in low-income multi-unit housing with large Russian populations CPA Chinese Youth Citywide Supported efforts for smoke-free public spaces including entrances and common spaces in multi-unit housing, farmers’ markets, taxis, bars, charity games, tobacco shops, etc. 2010–2013 BCGG Adult Citywide Advocated for smoke-free street events policy Freedom from Tobacco Adults LGBT Advocated for voluntary policies for smoke-free outdoor patios in bars San Francisco Apartment Association Adult Citywide Supported multi-unit housing disclosure policy in partnership with Dolores Street Community Services Girls After School Academy Youth Sunnydale Advocated for voluntary smoke-free policy at multi-unit housing in the San Francisco Housing Authority Vietnamese Youth Development Center (VYDC) API Youth Tenderloin Advocated for cleaning cigarette-litter and supported efforts to convert corner stores into healthy retail stores, which led to the creation of the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition YLI Latino Youth Mission, Bayview Advocated for Tobacco Retail Density Ordinance, which passed in 2013. Efforts started in 2007. 2014–2017 BCGG Young Adult Citywide Advocating for local policy that would ban the sale of flavored and menthol tobacco-products YLI Young Adult Mission Supporting efforts to reduce storefront tobacco advertising and replace it with community art murals Bay Area Community Resources Youth Citywide Supporting voluntary smoke-free multi-unit housing policies VYDC Youth Tenderloin Advocating for policies that would allocate more cigarette litter mitigation fees to the Tenderloin neighborhood and other neighborhoods with high concentrations of tobacco retail stores - Thank You: Bright Research Group

This report was prepared by Bright Research Group. An Oakland-based and women- and minority-owned firm, Bright Research Group specializes in evaluation, community engagement, and strategic planning for the public sector, nonprofits, collaboratives, and private entities working to achieve greater social impact.

- Download:

Policy Lessons Learned from Twenty Years of Community Capacity Building in San Francisco through the Community Action Model

Case Study Prepared by Bright Research Group

Creating Change by Building Community Capacity