“When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause-and-effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context, the proponent of the activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.”

- Introduction:

In 2014, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors adopted a policy to treat e-cigarettes as a tobacco product. Concerned about the rising use of e-cigarettes by youth and nonsmoking adults, the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project (TFP)—a project of the San Francisco Department of Public Health—provided policy proposals and educated the supervisors about e-cigarettes to inform this policy decision. As a result, San Francisco Health Code Article 19N prohibits the use of e-cigarettes wherever traditional cigarettes are prohibited, effectively limiting e-cigarette use primarily to street curbs away from building entrances and windows. The law also requires sellers of e-cigarettes to obtain a tobacco-retailer license. To educate the public about the new law, the TFP developed #CurbIt, a multipronged campaign that used social media, transit ads and traditional media to educate the public about the new law. This case study describes the strategies that led to San Francisco’s policy as well as lessons learned from the subsequent media campaign to raise awareness of the new guidelines. These lessons can help inform future campaigns in San Francisco and other jurisdictions.

What are E-Cigarettes?

The San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project is part of a growing community of public-health advocates and professionals who are concerned about the negative health impacts of—what has until recently been—the unregulated e-cigarette market. Electronic cigarettes were introduced in the United States in 2007. Electronic cigarettes (or e-cigarettes) are battery-operated devices that heat a liquid that generally contains nicotine, flavorings, additives and propylene glycol (e-liquid). When heated, the liquid in e-cigarettes creates an aerosol that includes several chemicals that have been known to cause cancer, birth defects and other public-health hazards commonly associated with traditional cigarettes.[i] In less than 10 years, the accessibility and popularity of e-cigarettes has grown significantly, with at least 466 brands of e-cigarettes being sold on the market, generating $2.5 billion in annual sales worldwide.[ii] While there are stringent federal and state regulations around the manufacturing, labeling, advertising and distribution of traditional cigarettes, e-cigarettes had not yet been regulated by the FDA or the State of California in 2013, when San Francisco tackled the issue.[iii] Public-health advocates had several concerns about the impact of e-cigarettes.

Common Names for Electronic Cigarettes

- E-cigs

- Vapes

- Vape pens

- Vape pipes

- E-hookahs

- Hookah pens

- Mods

Increasing Use Among Youth and Adults: Teen use of e-cigarettes surpassed teen use of traditional cigarettes in 2014.[iv] Nearly one in five young-adult (18 to 29 years old) e-cigarette users in California had never smoked traditional cigarettes.[v] In other words, even nonsmoking youth and young adults were using e-cigarettes. E-cigarette use was also on the rise among adults—the rate tripled in one year from 2.3 percent to 7.6 percent.[vi] The increasing presence of e-cigarettes in social and public settings had renormalized tobacco use, putting decades of effective tobacco-control policies at risk.

Targeting Youth: E-cigarettes are being sold in multiple candy and fruit flavors that are designed to be attractive to youth and children. E-cigarettes are also being used to inhale marijuana and hash oil, which are easier to hide from school and law-enforcement officials. Though tobacco companies have been banned from marketing traditional cigarettes on TV and radio since Congress passed the Public Health Cigarette Smoking Act in 1970, e-cigarettes were being widely advertised on these channels.

Poisonous E-Liquids: In addition, the e-liquids are poisonous and may be lethal to small children. California has seen a threefold increase in the number of calls to poison-control centers regarding young children who have ingested or been exposed to e-liquids.[vii]

Health Effects: There have been no long-term studies on the health effects of firsthand, secondhand and thirdhand e-cigarette usage. There is a general assumption about, and marketing of, e-cigarettes as producing water vapor instead of the potentially dangerous aerosol that is associated with nicotine and other cancerous chemicals. E-cigarettes are also being sold as tobacco-cessation devices to help people quit smoking; however, there are not validated scientific studies that show that e-cigarettes successfully helped smokers quit traditional cigarettes.[viii]

[i] Ron Chapman, California Department of Public Health, “State Health Officer’s Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat” (https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/Media/State%20Health-e-cig%20report.pdf), January 2015.

[ii] San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project, E-Cigarettes Fact Sheet (https://sanfranciscotobaccofreeproject.org/electronic-cigarettes/), 2015.

[iii] In 2011, the State of California regulated e-cigarettes so that they could not be sold to minors. Otherwise, the FDA and State of California did not have regulations in place for e-cigarettes until two years after San Francisco passed its local policy. Please note that in April 2016, the FDA expanded its regulatory authority to cover more tobacco products, including electronic cigarettes, cigars, hookah tobacco and pipe tobacco. The FDA will now regulate these products from the point of manufacturing, labeling and advertising to distribution. In addition, the State of California passed SB5/AB6, which adds e-cigarettes to the definition of tobacco—a similar policy modeled on San Francisco’s local policy.

[iv] Ron Chapman, California Department of Public Health, “State Health Officer’s Report on E-Cigarettes: A Community Health Threat” (https://www.cdph.ca.gov/programs/tobacco/Documents/Media/State%20Health-e-cig%20report.pdf), January 2015.

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Ibid.

[vii] Ibid.

[viii] Ibid.

- San Francisco's E-cigarette Policy:

Choosing a Policy Option

San Francisco subscribes to the Precautionary Principle as the basis for all environmental policy.[i] As a result, the San Francisco Department of Public Health had a responsibility to reduce e-cigarettes’ potential to harm communities. Chief among San Francisco’s concerns was how e-cigarettes were contributing to the renormalization of tobacco use for younger generations. Decades of tobacco-control policy had protected younger generations from exposure to secondhand smoke, targeted advertising and “positive” smoking icons (e.g., the Marlboro man). Through focus groups with youth on the e-cigarette issue, the TFP found that youth associated smoking cigarettes with cancer, heart disease, yellow teeth and other negative associations. However, for young people, e-cigarettes did not have the same association, with many adhering to the myth that e-liquids are harmless water vapors.

Local government bodies have limitations with respect to the types of policies that are realistic and enforceable. For example, passing a policy that would regulate the production or packaging of e-cigarettes was out of the purview of a local government like the City and County of San Francisco. However, San Francisco had passed dozens of policies over the years that restricted who could sell tobacco products (i.e., those with tobacco-retailer licenses) and where tobacco products could not be used (i.e., restaurants, bars, workplaces, doorways, schools, etc.). These two policy areas were the primary levers that San Francisco had to affect e-cigarette use.

Businesses and community members had been calling the San Francisco Department of Public Health as early as 2009, wondering about whether people were allowed to use e-cigarettes in places where traditional cigarettes were not allowed. E-cigarettes were emerging products, and their ingredients and impending popularity were not yet known. San Francisco International Airport was the first to take action to ban the use of e-cigarettes at the airport. The City and County of San Francisco followed next by passing an administrative rule that restricted e-cigarette use in health and social-service settings, e.g., hospitals and WIC (Women, Infant, and Children) clinics. In the meantime, researchers at UC San Francisco (UCSF) and Stanford University had started to test these products to better understand their ingredients.

Equipped with more information about the true content and potential for harm of e-cigarette products, the TFP started to meet with community stakeholders and policymakers to share this information, identify a shared policy proposal and generate support for action by the Board of Supervisors. Knowing the levers of control at the local-government level, the TFP decided to focus its policy efforts on restricting where e-cigarettes could be used and where they could be sold. However, the TFP had spent nearly 20 years creating numerous policies that restrict and control tobacco use in San Francisco. Revising each existing policy would be tedious and politically untenable. Instead, the TFP decided to support a policy option that would essentially redefine tobacco to include e-cigarettes, thereby retroactively applying all policies that prohibit tobacco use to e-cigarettes.

Making the Case

To make the case for this policy among the supervisors and community members, the TFP utilized two primary strategies. The first was to gather data about youth access to e-cigarettes. The second was to engage researchers to share the science behind the potential harms of e-cigarettes.

Every year, youth advocates—in partnership with the San Francisco Police Department and the Tobacco-Free Coalition, the community coalition overseen by the Tobacco-Free Project— conduct retail-store survey operations to monitor and enforce storeowners’ sales of tobacco products to minors. Coalition members and youth advocates had noticed that e-cigarettes were being used by many youth and that they were produced in youth-friendly flavors. As a result, the 2014 youth survey operation focused specifically on the sale of e-cigarette products to minors. Ten out of 11 stores sold e-cigarette products to minors during this operation. This localized data about youth access motivated policymakers to take these concerns seriously.

The testimony of researchers from UC San Francisco and Stanford University informed the policy-advocacy process with verifiable scientific data about the composition of e-cigarettes and their potential health harms and impact. During hearings in front of the supervisors, this research was used to debunk myths and arguments presented by e-cigarette users and supporters, or by supervisors who were on the fence. The testimony included research that refuted the claim that e-cigarettes release harmless water vapor and that they are effective tools for smoking cessation. UCSF organized over 10 researchers to testify at the supervisors’ meeting. Overall, the opposition was minimal and primarily came from medical-marijuana advocates, who were concerned that the policy would restrict patients’ ability to utilize marijuana for medicinal reasons.

Tobacco-Free Coalition members met with several supervisors and raised other concerns about e-cigarettes. Armed with local and scientific data, and concerned about the tobacco companies’ involvement in the targeted marketing of e-cigarettes to youth, Supervisor Eric Mar introduced and sponsored the policy at the Board of Supervisors.

The Policy Victory

The e-cigarette policy was introduced through the Rules Committee and passed with great support at its first hearing. The Tobacco-Free Coalition organized nearly 40 testimonies from supporters of the policy, including youth advocates who shared their concerns about e-cigarette use among their peers. UCSF researchers shared their reports and data about the increasing use of e-cigarettes and the harms associated with the chemicals inside e-cigarettes. Supervisor Eric Mar even took a puff from an e-cigarette in the chambers to demonstrate what it would mean if we did not pass this policy—after all, e-cigarettes were not considered tobacco and therefore were not covered by the city policy prohibiting smoking on public property. The policy was then referred to the Youth School Board, the Youth Commission, the Health Commission and the Small Business Commission. Tobacco-Free Project staff and Coalition partners presented about e-cigarettes to each of these groups and received anonymous support in advance of the full Board of Supervisors’ consideration of Supervisor Mar’s proposal.

The draft policy already had an exemption that provided an exception for medical-marijuana use, which allayed concerns from medical-marijuana proponents. Without any other opposition, the Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the e-cigarette policy, and it went into effect in April 2014.

San Francisco’s E-Cigarette Policy · An establishment must have a valid tobacco-sales permit to sell e-cigarettes. · The use of e-cigarettes is prohibited wherever smoking of tobacco products is prohibited by law. · The sale of e-cigarettes is prohibited wherever the selling of tobacco products is prohibited by law. · Exemptions include FDA-approved products marketed for therapeutic purposes and the use of e-cigarettes as a product for medical cannabis consumption. · The definition of “e-cigarette” is very broad. “‘E-cigarette’ means any device with a heating element, a battery or an electronic circuit that provides nicotine or other vaporized liquids to the user in a manner that simulates smoking tobacco.” - #Curb-it Public Education Campaign:

What Was the Purpose of #CurbIt?

Once the ordinance was adopted, the Tobacco-Free Project was confronted with the difficulty of enforcing the policy and informing the public about a new public-health concern. To help implement the policy, the Environmental Health section of the San Francisco Department of Public Health mailed a fact sheet to local retailers, merchants associations, city departments and other community spaces in the city, reminding them about the retailer license and providing them information about the new policy. However, the TFP saw a need for an effort to educate the broader community about the new restrictions around the use of e-cigarettes.

San Francisco decided to test innovative methods to engage and educate the San Francisco community to support de-normalizing e-cigarette use. TFP staff identified Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement funds that were allocated for public education and engaged a graphic-design firm to design a public-education and social media campaign focused on raising awareness about the new policy. The campaign was dubbed “#CurbIt”—a play on words that raised awareness about the new policy restricting e-cigarette use to the street curb.

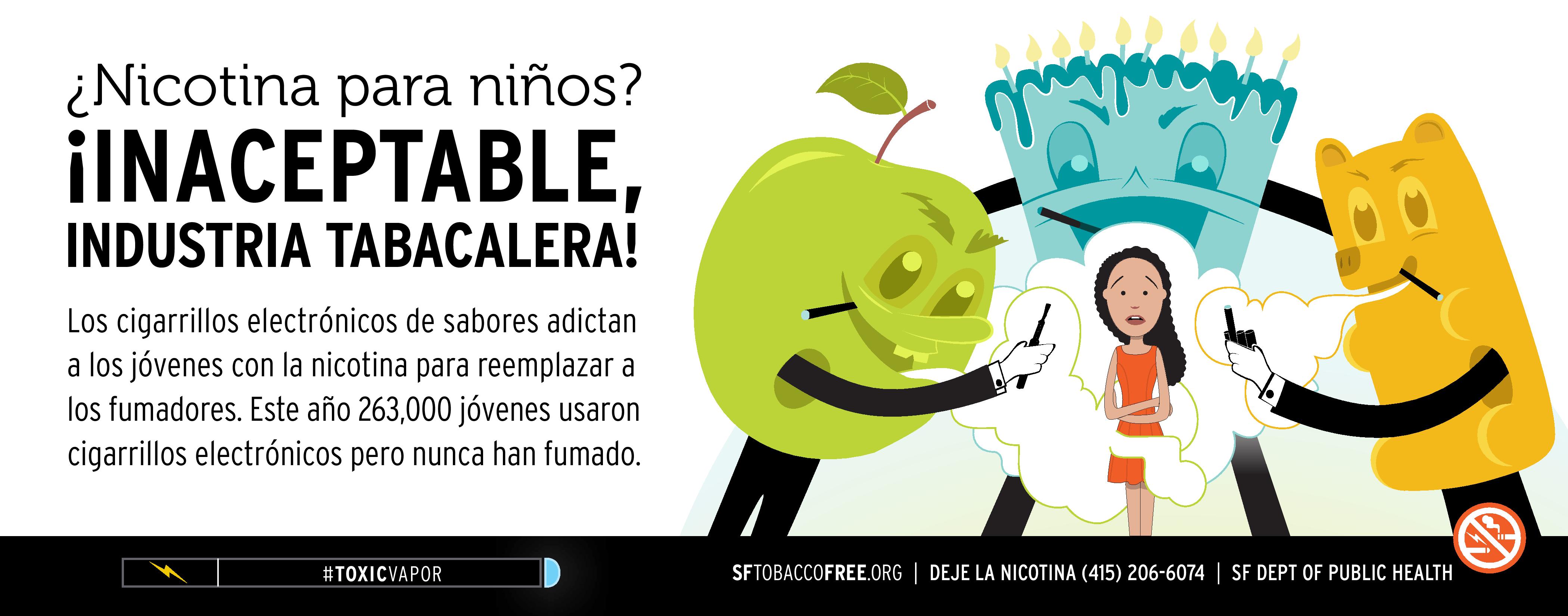

The ads and messages were guided by content developed by the California Tobacco Control Program, which had already tested several messages on thousands of participants. They narrowed down those messages on the basis of primary knowledge of specific ethnic communities and age groups, as well as insights gained from a focus group with local residents. The messaging was tailored on the basis of the preferences of these populations. For example, the African American residents in the focus group responded very strongly to draft ads that juxtaposed the Marlboro man to a recent ad of a rapper smoking e-cigarettes. In addition, youth responded well to animated images instead of images of real people. As a result, because the campaign aimed to reach youth as a primary target, all the ads used animated imagery.

In January 2015, the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Coalition launched the #CurbIt campaign, a three-pronged public-education campaign that deployed transit ads, traditional press outreach and social media strategies to educate San Francisco residents about the new law and raise the public’s awareness about the growing health concerns of e-cigarette use. This campaign was the first time the Coalition used social media to engage the public in tobacco-control-policy issues in San Francisco. #CurbIt was designed to debunk myths by using existing data and messaging in a way that appealed to youth, parents and San Francisco’s diverse communities.

What Was the Impact of #CurbIt?

Transit ads began appearing on rail, light-rail and bus lines in January 2015 at stations and stops, and in rail cars and buses. The media picked up several stories about the #CurbIt campaign. Two local print newspaper outlets, SF Weekly and the San Francisco Examiner, wrote favorably about the e-cigarette ordinance. The articles featured the #CurbIt ads, cited numerous statistics about e-cigarette use and access, and described how the e-cigarette industry is part of the tobacco industry’s efforts to get a new generation of young people addicted to their products. Stories about the policy and the #CurbIt campaign were also aired on local television and radio networks and published in local blogs or newspapers. Most stories were generally positive in nature and cited research that helped spread scientific evidence to the general community.

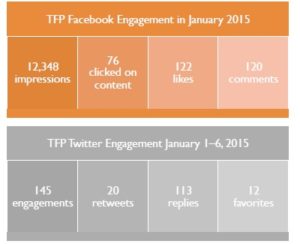

In early January 2015, the #CurbIt social media campaign started a lively online conversation that engaged opponents and proponents of the e-cigarette policy. Using Facebook and Twitter, #CurbIt sparked online conversations that provided the TFP with the opportunity to disseminate facts about the scientific research, data and other concerns related to the proliferation of e-cigarette use. The online conversation motivated some people to learn more by going to the TFP website, where additional information—including a fact sheet with over 70 research citations—could be found. More people viewed the website in January than ever before. Over 20% of all page views were on the #CurbIt page. Visitors also accessed other web pages to learn more about the Tobacco-Free Coalition’s work.

Although engagement was high, there was an unexpected flurry of negative tweets from e-cigarette users and advocates. The TFP needed to strike a balance between promoting their agenda while also debunking myths to control the messages related to the #CurbIt brand. While some social media responses may have been coming from local San Franciscans, there was a large response from residents of other cities, states and even countries, who felt that San Francisco was regulating harmless smoking-cessation devices. Over 30% of Twitter traffic originated in the United Kingdom. Consulting with a public-relations agency and media relations within the City and County of San Francisco, the TFP was able to develop a strategic response to social media in a measured and productive way. By the end of January, the conversation around #CurbIt online had wound down.

- The Future of E-Cigarette Policy and Public Education:

Lessons Learned

The public-health community has an important role to play in debunking myths about e-cigarettes.

The San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project played an important role in debunking the myths and advertising from the e-cigarette and tobacco industries. With little or no regulation from the state and federal government in place at the time, the TFP had to work with academia and leverage existing tobacco-control activities (e.g., decoy operations) to gather influential data that would mobilize key stakeholders and educate the public. On the basis of San Francisco’s experience, policies and public education related to e-cigarettes should gather local data and scientific evidence that debunk the two most common myths offered by e-cigarette advocates— 1) that e-cigarettes are effective smoking-cessation devices; and 2) that e-cigarettes emit harmless water vapor that does not cause harm to “vapers”—i.e., people who use e-cigarettes—and does not create secondhand-smoke hazards. In addition, the TFP needed to fight the tobacco industry’s efforts to market these products as glamorous, sexy and popular. The following key messages resonated with the San Francisco community and can be used for future policy or public-education campaigns related to e-cigarettes:

Effective E-Cigarette Messages For the first time in decades, we are seeing an increase in the number of youth smoking, because of their e-cigarette use. The tobacco industry is intentionally targeting youth with their product packaging and advertising. E-cigarettes are sold in over 7,000 flavors—many of which are youth-friendly flavors like Skittles or have packaging with youth-friendly images like Hello Kitty. E-cigarette ads glamourize rappers or other Hollywood-type stars who are using e-cigarettes. These icons are the new “Marlboro man” who appeal to younger people and, even more specifically, young African American youth. There is very little evidence that points to the use of e-cigarettes as smoking-cessation devices. Advertising is not targeted toward smokers who are trying to quit. There is no scientific evidence that shows that these devices help smokers quit. A lack of regulation of the issue has also led to these tobacco products being advertised on television again for the first time in generations. This new advertising is renormalizing smoking and could lead to increased rates of smoking. Contrary to industry claims that e-cigarettes emit harmless water vapor, research has found that e-cigarettes pollute the air with the emission of aerosols and nano-particles that contain harmful heavy metals and nicotine. E-cigarettes also expose non-vapers to secondhand smoke, just like regular cigarettes do. Social media can help public-education campaigns go viral and reach more people than traditional public-education efforts. However, social media invites opponents’ voices into the conversation, including the voice of those who are not residents of your jurisdiction.

Effective social media campaigns should assume that those who are most likely to engage may already have strong opinions on the issue or may want more information on the issue. Providing basic facts, data and statistics before promoting a specific campaign (e.g., #CurbIt) can help generate interest while also dismissing myths. Social media is a good forum for providing quick, short snippets of information. Tweets and Facebook posts should be backed up with a detailed fact sheet with cited scientific research that can also be shared to provide more information. Preparing in advance for a communications strategy to respond to strong opposition can help the campaign’s success. Partnerships with high-profile researchers like professor Stan Glantz of UCSF and others to support the #CurbIt campaign lent legitimacy to the data shared by the campaign. The TFP was able to disseminate targeted, scientific and factual messages in response to myths about e-cigarettes that appeared in the #CurbIt conversation.

In addition to engaging researchers, allied organizations and high-profile individuals should be engaged and educated about social media efforts before a campaign launches. This will allow allies to provide support for the Tobacco-Free Coalition’s messages through their own social media presence, spread the word through their networks and, when all else fails, drown out negative or incendiary commentary.

To help control the message, TFP learned a few tips about using social media platforms effectively:

- Pick two or three messages and stick with them. San Francisco’s priority was to tell people that a new law was in town, to inform them of the potential harms of e-cigarettes and to raise concerns about the targeting of youth.

- Limit the number of hashtags used. Having one hashtag allows staff to monitor the whole conversation in one streamlined location.

- Develop a response policy before using social media. Social media users can use inciting, derogatory or inappropriate language that can distract from the conversation or offend other users. There should be a clear policy that is shared with social media users and used by internal staff to report users or delete derogatory posts.

- Ensure that you have the staff time to do it. There must be a staff member dedicated to engaging and responding to the conversation while it is trending.

Progress on Federal and State Policies

San Francisco passed the e-cigarette policy in early 2014, two years before there was any additional action from the state and federal governments. In May 2016, Governor Jerry Brown signed a package of five tobacco-related bills into law. Among them is SB5/AB6, which adds e-cigarettes to the definition of tobacco in the same manner as, and with the same intended effect of, San Francisco’s e-cigarette policy. Effective in June 2016, the new state law changes the definition of tobacco products to include e-cigarettes, requires retailers to obtain a license to sell these products, requires child-resistant packaging and subjects e-cigarettes to all smoke-free laws.

In the same week, the FDA expanded its regulation of tobacco products to include e-cigarettes, cigars, hookah tobacco and pipe tobacco. This brings e-cigarettes under the same regulatory authority and requirements as those of traditional cigarettes. In addition, the FDA retroactively applied all public-health regulations to products that have been on the market since February 2007—which includes most brands of e-cigarettes. With these new regulations in place, manufacturers will need to register their establishments, report ingredients and place health warnings on product packages and advertisements, and they will be unable to sell “light,” “low” or “mild” tobacco products. FDA’s regulations go into effect in August 2016.

Now under regulation from federal, state and local bodies, the policies, systems and environment changes around e-cigarettes will help reduce the harm of e-cigarettes on communities. However, several years of unregulated marketing and use have resulted in rising use rates among youth and a more normalized perception of e-cigarettes among youth and adults. When state and federal policy is slow to move, local policy efforts like the one led by San Francisco can serve as a stopgap and a model for broader regulations. The lessons learned in this case study could serve to inform additional public-education messages around e-cigarettes as well as future policy efforts related to the next generation of products that the tobacco industry tries to introduce to the market.