- The Organization: What is the Good Neighbor Program?Mission

The mission of Literacy for Environmental Justice (LEJ) is “to promote the long-term ecological and human health of Southeastern San Francisco by educating and organizing youth around the principles of environmental justice and urban sustainability.”

The History of Literacy for Environmental Justice

Literacy for Environmental Justice is an urban environmental education and youth empowerment organization created specifically to address the unique ecological and social concerns of the community of Bayview Hunters Point in San Francisco and the surrounding communities of Mission, Potrero Hill, Visitacion Valley, and Excelsior. LEJ engages urban youth in traditional environmental problems by making concrete linkages between the state of human health, the environment, and quality of urban life. LEJ has found that once these inter-relationships are recognized many young people want to be involved in creating a “livable” city. Staff members teach and/or employ young people to research, design and organize educational neighborhood improvement projects and students leave the organization with skills and a shared experience of positive and visible work. LEJ offers free educational programs for public schools and paid high school youth leadership programs, and works both in the public school system and in partnership with other community-based organizations.

The Tobacco Free Project’s Community Action Model

The Community Action Model is used by all the community capacity-building projects funded by San Francisco Tobacco Free Project (TFP). The model is asset-based and builds on the strengths or capacity of a community to create change from within and mobilize community members and agencies to change environmental factors promoting economic and environmental inequalities. Fundamental to the model is a critical analysis that identifies the underlying social, economic and environmental forces creating the health and social inequalities that the community wants to address. Funded agencies undergo a process of selecting an “action” that is achievable, sustainable, and compels a group, agency or organization to change the place they live for the well being of all.

The Community Action Model includes the following steps:- Train participants (Community Action Teams).

- Define, design and conduct a community diagnosis to find the root causes of a community concern or issue and discover the resources to overcome it.

- Analyze the results of the diagnosis and prepare findings.

- Select, plan and implement an action based on the findings from the diagnosis.

- Enforce and maintain the action.

Context and History

Many ingredients and catalysts took place that brought together people and ideas which laid the foundation for the creation of the Good Neighbor Program. These include: community organizing around toxics issues 1989-present; a community survey of environmental and health issues 1999; a community forum that identified markets as a focal point for action 1999;

HEAP (Bayview Hunters Point Health and Environmental Assessment Program) good neighbor preliminary efforts in 1999 and 2000; participatory research on food security issues with SLUG Youth Envision Project (San Francisco League of Urban Gardeners) 2000-2001; ongoing efforts by the Environmental Health section to reframe environmental justice issues in the Bayview Hunters Point; and Health impact assessments on food security strategies.

- The Youth Advocates: LEJ recruited six to eight youth each year to work as community activists with its Youth Envision program to organize around the issue of food security in Bayview Hunters Point (BVHP). Youth advocates were paid $9 per hour and worked 4-8 hours per week.

Advocate Recruitment

High school students residing or attending school in Bayview Hunters Point were recruited as advocates. Some youth learned about the project through friends or relatives working within LEJ, some walked into the office and saw signs for hiring, and others were recruited through school presentations. During the interview process, LEJ looked for a sense of commitment, knowledge or passion about the issue, or a willingness to learn more about it. The youth were observed interacting with others and group dynamics as well as their own self-discipline. According to the project coordinator, of all the approaches used to recruit advocates, making the youth “feel they’re part of making a change in community” and giving them a sense of ownership in the project was most effective in attracting them and keeping them active.

When asked why they joined the project, advocates responded:

- “To better my community.”

- “To make a change in my community.”

- “Because they were here to support us.”

- “To help my community.”

Advocate Training

Beginning in February 2002, the youth advocates received ongoing training throughout the two years of the project. The Community Action Model (previously described) was used as the principal training tool. Specific trainings included:

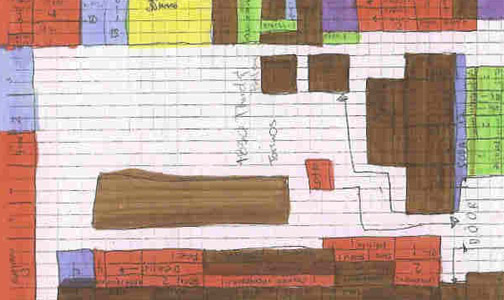

- Ongoing community health assessment training that included surveys, interviews, data collection (store diagrams), GIS mapping, and community observations (journal writing).

- Diversity training, including sessions on oppression, economic sustainability, and Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender and Queer awareness.

- Tobacco industry and the global economy.

- Food systems and environmental justice; industrial agriculture; fast food; genetically engineered foods; food access and distribution.

- The legislative process.

- Interviewing training.

- Presentation skills.

- Food preparation; healthier food alternatives; food systems.

- Public speaking.

- Self-esteem build-up/motivational speaking training.

- Media/ad designs.

Youth Envision advocates developed and practiced their advocacy skills by providing informational presentations to groups in San Francisco, Watsonville, Sacramento, Milwaukee, Oakland, and Marin County. At the Sacramento Ministerial Convergence, Youth Envision advocates spoke before thousands of people attending the conference about food security and anti-tobacco food subsidiary products.

Most of the advocates thought that the skills they learned in the project would help them in the future:

- “I plan to become very involved in policy and advocacy so most of the skills I’ve acquired are and will be beneficial to me in the future.”

- “I will use the skills I acquired to better present myself in future projects.”

- “I will use what I learned in help my community become a better, healthier place.”

The causes of food insecurity include supermarket flight from inner cities, transportation barriers, inundating inner cities with fast food chains and food that is high in salt, sugar, and fat. Food insecurity contributes to growing rates of diabetes and obesity – health concerns that rank high in inner city communities like Bayview.

Bolen, E. and Hecht, K. (2003, January). Neighborhood Groceries: New Access to Healthy Food in Low Income Communities.

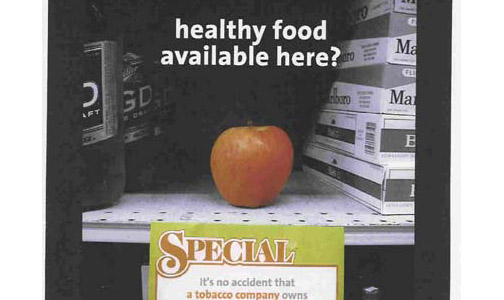

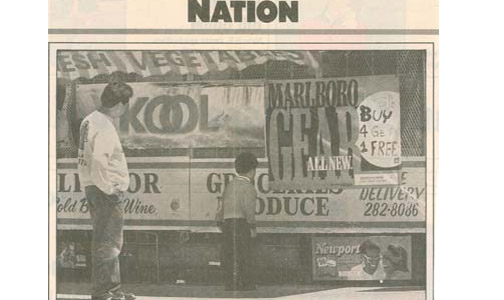

- Problem Being Addressed: Compared with more affluent neighborhoods, Bayview Hunters Point residents have limited access to high quality, fresh food, many have fewer options in the variety of foods that are available and, when groceries are available, pay much higher prices. The more than 30,000 residents of predominantly low-income Bayview Hunters Point (BVHP) lack access to culturally appropriate, affordable, and healthy food – the definition of food insecurity. The two closest grocery stores or supermarkets are an hour’s bus ride requiring three transfers. As in other inner-city neighborhoods that lack better alternatives, many BVHP residents are forced to rely on corner stores as their main food resource. Corner stores tend to carry alcohol, cigarettes, and non-perishable packaged and convenience foods of poor nutritional value. When fresh produce, dairy, and meat are available, they tend to cost consumers far more than if they purchased the same products in a supermarket. Lacking access to high quality food and fresh produce contributes to increasing rates of chronic diseases and obesity.While large tobacco corporations make the majority of their money selling tobacco products by aggressively targeting communities of color and low-income communities like BVHP, over the past 30 years some have diversified their holdings to include food products. Philip Morris/Altria, the largest of the tobacco companies, makes billions in worldwide revenues from the sale of their food subsidiary products from Kraft and Nabisco – found in 99% of American households and in more than 140 countries under 61 brands. Many Kraft/Nabisco products are targeted toward children and contain genetically engineered ingredients not yet approved for human consumption. Most recently, Kraft has been sued because their popular Oreo cookies contain trans fat, which has been linked to high cholesterol and heart disease. The lawsuit would ban the sale of Oreo cookies to children in California. In fact, Kraft/Nabisco are the second largest corporate food producers in the world and are major players in a corporate led food system that contributes to food insecurity worldwide.

- The Community Diagnosis: The goal of the Youth Envision Good Neighbor project is …

“to collaborate with local food retail establishments in Bayview Hunters Point neighborhood to promote an environment that encourages healthy living and improves the food resources of all the residents in the community.

As such, the replacement of tobacco subsidiary projects with healthy and locally produced food alternatives is essential to the health of the Bayview Hunters Point community.”

During the first year of the project, Youth Envision conducted a diagnosis of food security and tobacco food subsidiary issues in Bayview Hunters Point. The diagnosis was completed in late 2002. The data that was collected revealed the following findings:

Researching Good Neighbor Policies. Most of the Good Neighbor agreements existing in other cities nationally had originally evolved as a non-legal tool to develop partnerships between companies and communities to mitigate the effects of pollution and community health risks. The BVHP project was not directly fighting a polluting industry in the community but rather pursuing improvement in the community by working closely with small business merchants to stock healthier food alternatives and to limit the sales and advertisements of tobacco subsidiary products. Youth Envision thus adapted an agreement to reflect the specific goals of the BVHP project.

Health Food Access Survey. Youth advocates surveyed 130 residents regarding their perceptions and experiences in accessing healthy foods. Of those surveyed:

- 40% reported buying most or all of their food at a supermarket and not in their neighborhood.

- 20% reported getting their food from a corner store.

- 57% cited the high cost of food as a problem or barrier.

- 52% said poor quality food and 48% said the unavailability of food were big problems.

- 47% said that the bigger food stores were not accessible by public transportation.

- Nearly 25% reported eating fast food or take out most days or daily.

Further, 40% of respondents said that better quality and variety of foods at corner stores and/or the addition of a nearby farmers’ market or new/nearby supermarket would most help them gain access to healthier food.

Corner Stores Diagram. Youth advocates diagramed 11 corner stores along Third Street in BVHP and color-coded them to estimate the amount of shelf space dedicated to packaged food, alcohol and cigarettes, all other beverages, meats, produce, and non-food products. Their findings indicate the most accessible items in local stores were alcohol, tobacco, packaged foods, and non-food products. Fresh produce made up only 2% of the total products carried by the 11 stores (Figure 1).Store Survey of Kraft and Nabisco Products. Youth advocates then returned to the same 11 stores and counted the total Kraft/Nabisco products as a percentage of the total number of products sold in stores. They found that over 90% of cookies and nearly 80% of cereals and crackers in all the stores were Kraft or Nabisco products.

Economic Incentive Study. Youth Envision worked with a student intern from UC Berkeley who researched existing city-sponsored economic incentive mechanisms for small merchants in San Francisco. The resulting report was used to pare down a list of potential incentives for BVHP merchants who might participate in a Good Neighbor program.

Merchant Interviews. The youth advocates conducted interviews with five out of the eleven corner store merchants in the area. Merchants said the hardest part of having a business on Third Street was the danger and disruption of the local drug traffic and resulting neighborhood blight. The merchants had some ideas about improving store patronage, including advertising, a safer atmosphere, merchant education, more support from local community members, and store improvements or renovations.

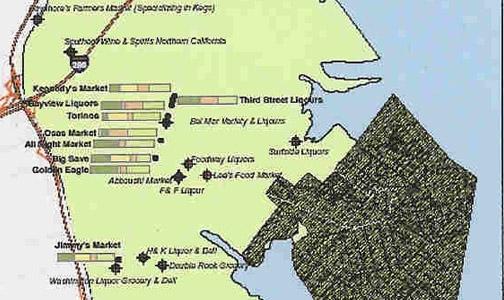

GIS Map. Youth Envision, in partnership with Crissy Field Center and Alex Lantsberg, completed a GIS map of the surrounding area. They found that the census tracts where the majority of the BVHP population lives are primarily hillside areas, while the local grocery stores are in the “flats” over one-half mile away. Existing public transportation requires about one hour and an average of three bus transfers from Hunters Point hills to get to the closest supermarket.

Replacement Products. Youth Envision advocates met with Rainbow Cooperative Grocery and other food coops and arrived at an agreement wherein Rainbow would make bulk, low cost and organic replacement products available to BVHP merchants who agree to participate in the Good Neighbor program.

- Changes Being Sought: GoalsTo combat the issues mentioned above, LEJ decided to focus on:

- Improving access to healthy food in existing corner stores, the primary food resource in the neighborhood, and

- Decreasing the presence of tobacco subsidiary products and tobacco and alcohol advertising in 11 of corner stores in BVHP.

- Strategies: The Action PlanLEJ’s action plan consisted of two principal strategies to reduce tobacco subsidiary food products and replace them with healthier food alternatives for residents living in Bayview Hunters Point: develop a sustainable, city sponsored Good Neighbor Program and implement the program components at a Good Neighbor Pilot Corner Store.

The Good Neighbor Program

What is a “Good Neighbor”?

A local retail food establishment that collaborates with city/community to promote healthy food access and to discourage activities that are detrimental to the well being of the community by stocking and advertising health promoting products, discourages unhealthy practices in the vicinity of the store, abiding by existing laws, takes part in commercial endeavors that promote environmental sustainability, and participates in activities that meet nutritional needs of local community residents.

During the project term, LEJ staff , advocates, and DPH health educators developed the Good Neighbor (GN) Program. The GN Program would be city sponsored and would partner with community-based organizations to encourage merchants to reduce tobacco ads and sales as well as increase healthier food products available to the community in exchange for city-sponsored incentives, including infrastructure improvements, store branding, free advertising, and cooperative buying opportunities.

A Good Neighbor store is defined as a local retail food establishment that collaborates with the city/community to promote access to healthy food.

Specifically, a Good Neighbor store must meet the following criteria developed by youth advocates, the project coordinator, community supporters, and community members:

Size. The establishment must not exceed 100,000 feet or 30K square feet.

Stock fresh produce. A minimum of 10% of items in the establishment must consist of fresh produce. The items must be diverse and include six separate varieties of produce. Additionally, owners are encouraged to carry appropriate products that are organic and locally grown.

Stock healthy foods. An additional minimum of 10% of items in the establishment must consist of healthy foods (for example not Kraft or Nabisco products). Owners are also encouraged to carry culturally appropriate products.The store must participate in programs that make food affordable and accessible such as Food Stamp, WIC, and related programs.

Adhere to environmental standards and all existing policies and codes that address loitering, cleanliness and safety.

Limit tobacco and alcohol advertising, promotion, and sales. The owner will eliminate all outdoor advertising of tobacco and alcohol products, and will not place indoor tobacco or alcohol advertising below three feet height measurements.

Adhere to all laws regarding illegal transactions including sale of tobacco/alcohol to minors.

Good Neighbor Pilot Corner Store

Based on the diagnosis results, LEJ also identified a store in the BVHP to pilot the Good Neighbor program. LEJ’s Youth Envision led the campaign to promote the Good Neighbor store, to encourage support, patronage, and recognition by the community, and to include information about the benefits of good nutrition and the dangers of tobacco subsidiary products while encouraging consumers to purchase healthier foods. LEJ youth advocates piloted alternatives to tobacco subsidiary products in BVHP corner stores and introduced the GN criteria. In exchange for participation, the pilot corner store merchant received up to $1,000 to purchase the pilot foods, a selection of energy efficient upgrades, free advertising in the community newspaper, the Good Neighbor store brand, and in-stores promotional activities

provided by Youth Envision. The pilot corner store partnership is intended to be a model for working with corner stores in neighborhoods throughout San Francisco.

- Implementing the Action Plan: LEJ worked with a coalition of public agencies and non-profits to create a sustainable means by which small merchants would be supported to provide healthy, affordable, non-subsidiary food products and produce with incentives provided by city government and the local community.

In response to Youth Envision’s proposed Good Neighbor Program and proposed pilot corner store, San Francisco District 10 Supervisor Sophie Maxwell established the Good Neighbor Task Force in September 2003 to research ways to make the GN Program sustainable and to improve food access and the quality of foods available to BVHP residents. The Task Force was made up of representatives from LEJ, the S.F. Department of Public Health, the S. F. Redevelopment Agency, the Department of the Environment, the Hunters Point Health Assessment Taskforce, and community leaders.

The Task Force met several times from September through the end of 2003. During that time, the group concluded the research and information gathering stage of the policy initiative, and designed the Good Neighbor Program as an incentive-based program to be housed within a city agency with which city merchants typically interface. The Task Force worked with a variety of city agencies, including the Mayor’s Office of Economic Development and the Mayor’s Office of Community Development, to define roles and levels of participation.

The LEJ project and the GN Task Force developed a list of Good Neighbor Program incentives that would be provided by its various members and others, as follows:

Taskforce Member Incentives

LEJ

Store branding, external and internal product promotions, outreach, and education to the residential community

S.F. Power Coop

Energy efficient upgrades (such as lighting and refrigeration), energy audits, education, and outreach to the business community

S.F. Department of the Environment

Funds the Power Coop and would provide networking and outreach

S.F. Redevelopment Agency

Provide future façade improvements to existing buildings

Mayor’s Office of Economic Development

Act as administrative and parent housing agency for the GN coordinator and provide funds to sustain the GN program

Rainbow Grocery

Collective buying of natural foods for participating merchants

S.F. Produce Market

Assist in marketing produce interior layout designs in stores.

SFDPH

Health promotion and prevention training concerning CAM, tobacco control and other health issues and policies.

Whole Foods Corp

Provides volunteer technical assistance to improve the interior produce section display.The Task Force met with Supervisor Maxwell in November 2003 to introduce the outline of the Good Neighbor Program and related materials, and scheduled further presentations with the San Francisco Commission on the Environment, the Project Area Committee, and the BVHP Merchants Association.Meanwhile, Youth Envision advocates worked with a graphic designer, Chris Ree, to develop a campaign logo, message, and conducted a media outreach campaign for the Good Neighbor (GN) pilot corner store. Media campaign products include:

- GN seal/poster as a trademark logo for all Bayview GN stores.

- GN stickers produced to target and educate the youth population about food security and anti-tobacco activism.

- GN postcards to be used for outreach and education with information on the back.

- GN canvas bags used for outreach, education and to promote sustainability. Includes educational materials about healthy food, tobacco corporations, and tobacco subsidiary products. The bags are given to participants attending the GN store launch, supporters, and community members.

- Bus shelter designs to advertised the campaign to the BVHP community specifically addressing issues of food access and tobacco subsidiary availability.

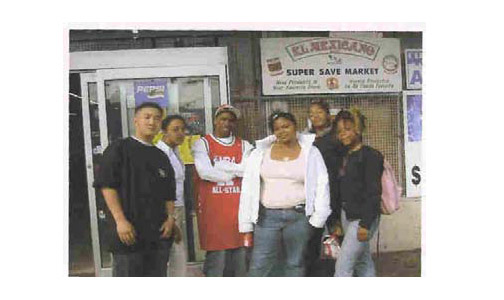

On December 19, 2003, Youth Envision officially launched the opening of its first Good Neighbor Store pilot partnership with Super Save Grocery, the largest store on Third Street in BVHP, with a neighborhood celebration. The event featured street performers dressed in fruit and vegetable costumes, youth speakers, food taste testing, and giveaways of new food items. In addition to Youth Envision, event sponsors included the Tobacco Free Project, S.F. Energy Cooperative, and the office of Supervisor Maxwell, who promised Youth Envision that the project would be adopted and implemented by a city agency. During this time, LEJ released also its bus shelter advertising campaign in the community.

At the conclusion of the first two-year funding period (December 2003), TFP contractors that had demonstrated significant progress towards their goals were provided with six months of additional funding. LEJ was selected as one of the providers. During the six month extension period, LEJ committed to finalizing the merchant agreement, evaluating the partnership, maintaining and further strengthening the Good Neighbor program with Super Save, continuing to market the Good Neighbor Program, conducting additional outreach and education, continuing to raise awareness, and sustaining the Good Neighbor Program.

- Outcomes: Finalized agreement with Super Save Grocery: Pilot Corner Store

A Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) was developed and signed by LEJ, the SF Community Power Cooperative, and Super Save Grocery as partners in the Good Neighbor incentive program for the period April-June 2004. The MOU defines responsibilities and timelines for each partner, as follows:

Memorandum of Understanding, April 1, 2004-June 30, 2004

LEJ

- Implement publicity and marketing campaigns including a local media campaign, in-store promotions, and advertising of both the GN store and the project itself

- Monitor program compliance

SF Community Power Coop

- Provide energy efficient refrigeration units

- Improve the interior of the GN store by seeking assistance from partnership agencies such as the SF Produce Market

Super Save Grocery

- Stock fresh produce and healthy foods at affordable prices.

- Comply with environmental standards, existing policies and codes that address loitering, cleanliness and safety

- Limit tobacco/alcohol advertising, promotion and sales

- Comply with laws regarding illegal sales of tobacco and alcohol to minors

Ongoing marketing of Good Neighbor pilot store

LEJ distributed coupons for Super Save and featured a cooking contest during the Earth Day event on April 17, 2004. Taste testing has been initiated to get consumers to try some of the new food. Currently, according to Sam Aloudi, SuperSave Manager, the produce section amounts to 30% of his total sales in the store, a dramatic increase compared to the 5%-10% prior to his involvement with the GN program. Finally, in late June, LEJ was able to get staff from Whole Foods Corp. to provide volunteer technical assistance to Super Save to improve the interior display of its produce section.

Removing tobacco ads

The GN criteria states that merchants participating in the program will eliminate all outdoor tobacco and alcohol advertising, and all such ads below 3 feet within the store. In a follow-up interview, the manager of Super Save stated that he is now more likely to remove other tobacco and alcohol advertisements posted in the store by industry distributors.

Sustaining the Good Neighbor ProgramLEJ project staff and the GN task force continue to work with a variety of city agencies to define roles and level of participation including defining a lead city agency to institutionalize and sustain the program. The Mayor’s Office of Economic Development has been identified as the potential acting administrative and housing parent agency of the GN program. Other city and community-based organization partners include San Francisco Department of Public Health, Department of the Environment, and the Redevelopment Agency, Mayor’s Office of Community Development, Literacy for Environmental Justice, Supervisor Maxwell’s office, other community-based organizations, and potentially outside funders/foundations that are interested in expanding the program. An MOU for participating agencies has been drafted for July 1, 2004-June 30, 2005.

The GN task force has developed a two-year workplan for the Good Neighbor Program, which is being implemented by a project coordinator and will be governed by the Good Neighbor Advisory Committee (GNAC), composed of individuals from numerous partner organizations and city agencies. As part of the two-year GN program workplan the project coordinator will do outreach, recruitment and orientation to eight food retailers in the BVHP. Other duties include materials and program development, coordination with city and community programs providing GN incentives, reporting to the GNAC and event planning. Over the course of the two years, it is hoped that eight new/existing food retailers will become GN retailers and participate in the program by signing a GN Retailer Agreement. The GNAC will meet on a quarterly basis and review all progress towards implementation of the program.

Outreach, education, and raising awareness

A power point presentation was created to aid Youth Envision advocates to present the Good Neighbor Program to CBOs, city agencies, San Francisco Food Alliance, and other community members. Oral presentations were made for BVHP Project Area Committee, National Kellogg’s Food and Society conference, and Supervisor Sophie Maxwell, and youth presentations and workshops continue to be given locally and nationally.

Youth Envision has conducted a second community survey of 200 residents to better understand how the BVHP community defines “healthy food” and is engaged in the laborious task of analyzing open-ended questions.

A Good Neighbor brochure has been drafted and is waiting for final language from various city agencies about incentives that they will be offering. The brochure will be given to participating merchants or merchants interested in learning more about the GN program.

- Challenges: Maintaining a core group of advocates

Several factors influenced the difficulties inherent in maintaining a core group. These include:

- Staff changes. The original coordinator retired from LEJ in August 2002 and was replaced by a new project coordinator.

- Transportation. The transportation infrastructure in Bayview Hunters Point is extremely poor and can take youth up to one hour to travel from their school to the project office.

- Youth commencement. Several youth graduated from the program and left to attend college (a success for them, but a program challenge).

- Extracurricular conflicts. Some of the youth advocates were athletes and at times their schedules competed with program attendance.

Introducing new food into a community

Early in the project during the interviewing process, BVHP corner store merchants expressed considerable skepticism about the sale worthiness of organic produce. They were concerned about changing existing inventory and cost. According to one merchant, “Organic food is expensive. People don’t have the awareness of organic in this neighborhood, and if it is more expensive, they won’t buy it.”1 The lack of awareness among neighborhood residents about what “organic” means has been, in fact, one of the greatest obstacles Super Save has encountered. There was no demand for organic projects from regular customers either before or after the Good Neighbor program began, in part because it costs a little more and because many people have misconceptions about the value of organic food and confuse it with diet food. Further, as in most low income areas, the community is inundated with the availability and aggressive marketing of nutritionally inadequate but relatively inexpensive fast food.

Creating a broad coalition

During the two and one-half year project, LEJ staff and advocates nurtured relationships with city agencies, community groups, and other nonprofits. This took place during a particularly difficult fiscal period in city government. The process involved in creating a sustainable GN program that would promote access to nutritious foods was lengthy and unpredictable. In addition, staff and task force members learned together, how to navigate city policy structures and systems. DPH health educators worked in partnership with LEJ to problem solve and provide training and technical assistance throughout the process.

Creating a broad coalition had both advantages and disadvantages. On the pro side, the more people involved the better because many different sectors got to know the project and help push it forward. Working collaboratively also provides good support for the project having different city agencies supporting it. On the other hand, agencies operate with different timelines and budget constraints. Because of different funding resources and timeline availability, agencies weren’t always able, for example, to provide funding for incentives when they were needed.Keeping the process going

Project staff and advocates juggled a variety of tasks during the project term. These involved everything from community-based participatory research, policy development, community organizing, media advocacy, and learning about entirely new systems and issues such as the links between tobacco transnationals, their food subsidiaries, and food security. In sum, Youth Envision had the work they were doing with Supersave and the overall Good Neighbor movement work going on at the same time. Again, DPH health educators worked in partnership with LEJ to problem solve and coordinate.

Limited resources

Currently, the program’s funding is sufficient to allow one coordinator and eight youth advocates to work on a part-time basis. Lack of time and resources limits the amount of work and the ability to fully address the issue of food insecurity in the community.

Need to integrate issues

Finally, improving community health includes increasing access to healthy foods. Equally as important in the movement to improve community health is the integration of efforts addressing other injustices present in the community, such as violence, environmental justice, poverty, racism, and sexism.

- Lessons Learned: Working with young people

This project reaffirmed the power of young people as advocates and outreach workers. Their motivation to make positive change in their community is in large part based on their own firsthand experience out of which they can speak personally about the issues. Youth have enormous creative energy in seeing this type of work move forward because it so directly affects their own lives, and those of their families and friends. One of the most challenging aspects for the youth was learning that changing attitudes and actions, and developing strategic ways of sustaining their work takes both time and patience.

Educating the community

Youth advocates found that winning space in a grocery store for organic and other healthy foods was only the beginning of a larger community education campaign that needed to be undertaken. The ways in which people think and act about food are different in different cultural groups. It is important to raise awareness about nutrition, and not impose new ideas in a cultural vacuum that might be received as offensive or disrespectful. Giving customers a chance to sample new products and produce (as done in many supermarkets) is one way to assist in this process.

Providing assistance to GN storesSuper Save needed assistance in displaying produce to make it more appealing to customers.

Together, the youth advocates and the Super Save manager decided to disperse GN products throughout the store rather than keep them confined in one section. The youth also produced “shelf-talkers” for selected non tobacco- subsidiary products that Super Save carries to bring more attention to each individual product. More signage will also be added in the store to bring more attention to the fact that the store is carrying non-tobacco subsidiary products. Finally, in late June, LEJ was able to get staff from Whole Foods Corp. to provide volunteer technical assistance to Super Save to improve the interior display of its produce section.

- Methods: This case study was developed using the following resources:

- Progress reports submitted by LEJ

- Research conducted by Kate MacLaughlin, a UC Berkeley graduate intern, for the project. Her report is entitled “Making Good Neighbors: Creating Food Security with Small Food Retailers in Bayview/Hunters Point” in Spring 2003. The report explored potential regulatory mechanisms and economic incentives that the City of San Francisco could provide for the Good Neighbor Program.

- Pre/post skills inventories administered by evaluator to Envision Youth advocates

- Media clippings

- Interview with Cece Carpio, Youth Envision Coordinator

- Good Neighbor Template (a text document that was written during the project period to chronicle the series of events that led to the successful creation of the GN project)

- Power Point Presentation materials

- Consultation with San Francisco Tobacco Free Project staff

- Other GN materials

- Credits:

Prepared by Polaris Research & Development Diane F. Reed For the San Francisco Department of Public Health Tobacco Free Project July 30, 2004

LEJ received funding for its Youth Envision program from the San Francisco Department of Public Health’s Tobacco Free Project. Funding was provided to implement the Community Capacity Building Process to replace tobacco food subsidiary products in corner stores in the Bayview Hunters Point community with healthier food alternatives and reduce tobacco and alcohol advertising at corner stores.

- Download: case study

Download the case study here.

Literacy for Environmental Justice (2004)

Good Neighbor Program

Bayview Hunters Point residents have limited access to high quality, fresh food.