- The Organization: What is the Mission Housing Development Corporation?Mission Housing Development Corporation (MHDC) was formed in 1971 to preserve and develop the Mission District by protecting low-income and predominantly Latino and other people of color residents’ right and access to quality and affordable housing. In 33 years, MHDC has constructed or rehabilitated nearly 1,300 units of affordable housing, ranging from multi-family and senior developments to historic residential hotels for the formerly homeless; created active tenants associations and service-enriched community environments in its developments; provided quality property management in partnership with its property management subsidiary, Caritas Management Corporation. MHDC currently has 462 additional units of affordable senior and family housing in development in the Mission District, Excelsior and Western Addition neighborhoods.

Inside and outside of MHDC’s developments, MHDC’s Supportive Housing and Resident Programs work has built a high level of resident engagement in neighborhood safety, economic development, and community health campaigns. This active engagement, in building the health, economic and civic welfare of the residents, has been key to MHDC’s success in maintaining the safety, stability and affordability of its housing for low-income people. MHDC’s Resident Programs also engages the communities outside of its developments to help integrate the residents of its developments into the larger community and improve the wellbeing of the community as a whole.

MHDC’s Resident Programs operates on the principles that they work to raise the voice of its low-income residents, by helping to develop their active participation and build leadership, to confront collaboratively those issues in their community that most impact the quality of their lives. MHDC’s Youth Community Health Organizing Project (YoCoHOP) is a outstanding demonstration of these principles.MHDC has been involved with the San Francisco Tobacco Free Project (TFP) for several years, receiving funding for a variety of projects, including advertising compliance in neighborhood stores, youth purchases of tobacco, getting the school board not to purchase tobacco subsidiary food products, and promoting alternative products. MHDC also received TFP funding for its current Youth Community Health Organizing Project (YoCo-HOP) YoCo-HOP is a Mission District youth group committed to improving the health of the Mission through community organizing and advocacy to address the influence of tobacco companies in their neighborhood.

- Strategy: The Tobacco Free Project’s Community Action ModelThe Community Action Model is used by all the community capacity-building projects funded by San Francisco Tobacco Free Project (TFP). The model is asset-based and builds on the strengths or capacity of a community to create change from within and mobilize community members and agencies to change environmental factors promoting economic and environmental inequalities.

Fundamental to the model is a critical analysis that identifies the underlying social, economic and environmental forces creating the health and social inequalities that the community wants to address. Funded agencies undergo a process of selecting an “action” that is achievable, sustainable, and compels a group, agency or organization to change the place they live for the well being of all.

The Community Action Model includes the following steps:- Train participants (Community Action Teams).

- Define, design and conduct a community diagnosis to find the root causes of a community concern or issue and discover the resources to overcome it.

- Analyze the results of the diagnosis and prepare findings.

- Select, plan and implement an action based on the findings from the diagnosis.

- Enforce and maintain the action.

- The Youth Advocates: Recruitment

YoCo-HOP hired and trained a total of 12 youth advocates. While they were with the project at different times, 10 remained with YoCo-HOP through December 2003. Most youth were recruited from MHDC’s family buildings and were hired from two buildings in particular, Maria Alicia Apartments and Juan Pifarre Plaza. The youth were 14 to 16 years of age. Others were hired from outside the MHDC system. Recruitment was conducted through flyers that were posted in the various buildings, targeted outreach to youth that were active in the buildings, meetings, and presentations. Hiring the youth advocates from within MHDC’s family buildings and the surrounding neighborhoods has provided greater interconnectedness and cohesion among the group.

The youth advocates reported joining the project for a variety of reasons:

- “I was interested in learning more about the risks of secondhand smoke because I am around it, and I also wanted to help other people avoid it.”

- “I wanted to learn something new while helping my community.”

- “To learn more, learn new skills and help my community at the same time.”

- “To get real life experience.”

- “Because my friends said it was a good way to improve my community.”

- “To improve on and learn new skills and I am against tobacco.”

YoCo-HOP sought a balance among high achieving youth and those that were not doing as well in school, and looked for a variety of skills, including:

- Ability to express themselves well

- Positive attitude about working with other youth they did not know

- Having experience working with other youth

- Enthusiasm and willingness to take on a cause unfamiliar to them

- Willingness to participate, cooperate, and openness to working in the community

Based on her own experience in the program, one youth advocate described personal characteristics that she felt would be important to bring to a project of this type. “Being friendly and having respect for themselves and others. Having experience, having conversations with others, and being interested in what they do and knowing about what they should do.” The MHDC Director of Resident Programs thought that the interaction youth advocates had with each other and the community was “like receiving indirect mentoring.”

The youth began the project working two days a week, three hours per day, with an occasional extra weekday or weekend day. Each advocate received a stipend of $125 per month. In May 2003, the advocates received an additional $75, increasing their stipends to $200, in exchange for additional responsibilities and working one additional weekday for two hours. In addition to their stipends, the youth receive a youth fast pass every month and other incentives, such as providing food during meetings, which have played an important role in maintaining retention and a high level of participation.

“I live in Maria Alicia Apartments and I have grown up in the Mission, I work at Yoco-HOP because I want to learn what I can do to improve my community… I used to be really shy and now with all the trainings that we have had it has been easier to communicate with people.”

Emmanuel, 16 years old , 11th grade, El Camino High School

Advocate TrainingAdvocate training began in March 2002 and was ongoing over the next 18 months conducted by MHDC staff and community organizers. The trainings and advocate meetings are conducted in a participatory manner, integrating icebreakers and group and community building activities to create a cohesive, comfortable, and dynamic group. In addition to drawing on the rich and varied experience of MHDC staff, members from the community, community organizers, and staff from other community organizations are regularly invited to interact with the youth and share their knowledge, experience, and skills.

Two-hour trainings were held about twice a month and were provided on a variety of subjects, topics, and issues. Youth learned about tobacco industry practices targeted youth and youth of color, globalization and economic impact on some U.S. communities, community organizing, gentrification, the history of the Mission District, facilitation skills, public speaking, running an effective meeting, media advocacy, and the Community Action Model.

One series of trainings included conflict resolution, team building, skills building, and trust building provided by an education consultant based on Augusto Boal’s Theatre of The Oppressed that applied theories of education through drama to raise awareness about racism, systematic oppression, homophobia, and classism. This series helped to tease out rough edges in the group, brought the group closer together, and helped the youth with their public speaking roles as tobacco control advocates and in their interpersonal relationships at work and in school.

In addition to in-group trainings, YoCo-HOP advocates also participated in various collaborative trainings with other community organizations and with San Francisco Tobacco Free Coalition member organizations to help support respective campaigns.

- One such training collaboration supported the Youth Skills Project in a signature gathering campaign to ban smoking outside building entrances during San Francisco Carnaval in Spring 2003.

- Another involved YoCo-HOP and Literacy for Environmental Justice in their Good Neighbor Program campaign efforts through participation in a joint training on local government political structures, policy change, and identifying and targeting key policy makers conducted by the MHDC Director of Resident Programs.

“What motivates me to do my TFP work for YoCo-HOP is that I wish tobe involved in community activity, in my community and in all of my friends communities. I am from the Western Addition.”

Greg, 14 years old , 9thgrade, Mission High School

The youth advocates interviewed towards the end of the project felt that the tobacco control project activities and training were culturally appropriate. Most were satisfied with the training they received and felt they would use a lot of the skills they learned in the future:

- “I can use my skills to inform people about the risks from secondhand smoke. I can use my skills to outreach to my community.”

- “I will use these skills to do similar projects in my community.”

- “I’ve learned the responsibility of holding a job. I think I learned how to hold a job for a long period and that will help me in the future.”

- “Public speaking, for example. It will be a great benefit to me in my future.”

- “I might have to do a class presentation, write a resume, or apply for a job and I learned how to do those things.”

- The Problem Being Addressed: Secondhand or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS) is a serious health hazard for nonsmokers, particularly children. ETS contains over 4,000 chemicals and at least 40 known cancer-causing chemical agents. Nonsmokers with high blood pressure or high cholesterol have a considerably greater risk of developing heart diseases when exposed to secondhand smoke which causes about ten times as many cardiovascular deaths as cancer deaths. According to the Environmental Protection Agency (EPS), secondhand tobacco smoke is a carcinogen that is responsible for approximately 3,000 lung cancer deaths annually in U.S. nonsmokers.Exposure to secondhand smoke increases the risk of lower respiratory tract infections such as bronchitis and pneumonia. The EPA estimates that each year, between 150,000 and 300,000 of these cases in infants and young children up to 18 months of age are attributable to exposure to ETS, of which between 7,500 and 15,000 will result in hospitalization. According to the same report, an estimated 200,000 to 1,000,000 asthmatic children have their condition worsened by exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

- Community Diagnosis: In designing a community diagnosis, YoCo-HOP youth advocates researched how secondhand smoke drifts, the health impact of secondhand smoke, and legal implications on the internet and at the library. The advocates met with health educators and inspectors from the San Francisco Department of Public Health. They developed an 11-question survey in English and Spanish and interviewed 67 families living in five MHDC buildings to determine the feasibility of passing a smoke free policy.

Resident Surveys in MHDC Family Buildings

YoCo-HOP youth advocates conducted surveys during the Summer of 2002 among residents living in five MHDC family buildings, including Maria Alicia, Dunleavy, Plaza del Sol, Mariposa Gardens, and Juan Pifarre Plaza. The buildings were chosen because they were multi-family buildings, housing many families with children.

Surveys were conducted in Spanish and English over the course of four weeks. The youth went door to door in every building, interviewing residents in their homes, one building at a time. The surveys consisted of 13 questions and took about seven minutes to complete. The questions were intended to gauge the attitudes of residents towards secondhand smoke, their knowledge of the harm of secondhand smoke and their openness to implementing smoke-free policies in their building. The youth completed 67 surveys and learned how to input the survey data into a statistical program with the technical help of the San Francisco Tobacco Free Project. They then analyzed their findings as a group.

Overall survey highlights include:- 82% of households reported having no smokers in their homes.

Of those who do smoke:

- 91% smoke on the sidewalk

- 60% smoke on the balcony

- 50% smoke in the courtyard

- 20% smoke in their apartment

- 87% of respondents said that secondhand smoke bothers them

- 72% of respondents knew about the damage that smoking can do

When asked where people should be allowed to smoke:

- 39% said the sidewalk

- 35% balcony

- 33% designated smoking areas

- 31% courtyard

- 87% said it bothered them when people smoke in common indoor areas

- 67% said it bothered them when people smoke in common outdoor area

- 77% of respondents said they would support rules restricting smoking in outdoor common areas

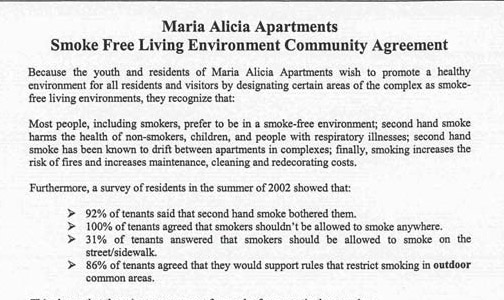

- Developing an Action Plan: In September 2002, the youth chose Maria Alicia Apartments – a 20-unit multifamily building housing 81 residents – at 16th Street & Valencia as the site at which they would introduce and facilitate a smoke free policy. The number of surveys collected at Maria Alicia Apartments represented a larger percentage of the building than at the other sites. Maria Alicia residents also demonstrated a high level of interest for a smoke-free living environment. Ninety-two percent of tenants reported being bothered by secondhand smoke. Eighty-six percent of respondents said they would support rules restricting smoking in outdoor common areas, and 92% said they would support rules restricting smoking in indoor common areas.

The youth advocates focused their efforts on developing four proposals for a smoke free policy at Maria Alicia and studying survey results to identify which proposal would be most achievable with the residents. The types of smoke free policies considered were:

- Phasing in smoke-free units in all or part of the building to be achieved through attrition (when a smoker vacates) or over a period of years.

- Designating specific areas as smoke free, such as separate wings, patios, areas where children play, or hallways that can be designated for smokers and nonsmokers.

- Prohibiting smoking in common use areas, such as lobbies, hallways, balconies, doorways, laundry facilities, recreational rooms, playgrounds, etc.

- Requiring an additional security or cleaning deposit for smokers to cover additional cleaning expenses caused by smoke damage.

In April, YoCo-HOP met with managers and the executive director of Caritas Management Corporation to present the proposed policies for the building. Caritas informed the youth that 8 they had

Smokers are not a federally protected class … the courts have not recognized a fundamental constitutional right to smoke, even in one’s own home.

With the help of TFP, YoCo-HOP researched additional information about the legality of introducing smoke free policies in publicly subsidized housing. They found no specific statutes or regulations to prohibit Maria Alicia residents or its management company, Caritas, from adopting smoke free policies. Smokers are not a federally protected class, meaning that the courts have not recognized a fundamental constitutional right to smoke, even in one’s own home. Where the Supreme Court has not designated an activity as a fundamental constitutional right, it will generally uphold government regulations that are rationally related to any conceivable legitimate objective of government.

State and local governments have already passed laws restricting smoking in many public areas, including:

- Health & Safety Code 1596.795 prohibits smoking in a private residence that is licensed as a family day care home during hours of operation;

- Health & Safety Code 118875 et seq. (California Indoor Clean Air Act of 1976) prohibits smoking in all public buildings and transportation;

- Labor Code 6404.5 prohibits smoking in enclosed work places including the common areas of apartment or condominium buildings or complexes if they are enclosed and places of employment.

- Health & Safety Code 118910 provides authority to local governments to completely ban smoking or regulate it to any lesser extent.

Federal and state anti-discrimination laws were also researched. Pursuant to the Federal Fair Housing Act, 42 USC 3601 et seq., discrimination in housing is prohibited on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, marital status, national origin, ancestry, familial status, age, or disability. Again, smokers per se are not a protected class. Further, “no smoking” policies prohibit only the activity of smoking within a designated area, not the smoker themselves. Smokers are thus not being discriminated against since the ban is on a specific activity and not directed at the individual. Thus, implementing a “no smoking” policy becomes the legal equivalent of other lease and contract restrictions and conditions, such as no pets clauses. The California Legislature has given authority to local governments to regulate smoking and there is no contrary authority on the federal or state level that would prevent local government from requiring a “no smoking” policy as a condition for a publicly subsidized housing complex.

Passing a Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement at Maria Alicia

Having found no legal barriers, and with the support of Caritas, YoCo-HOP youth advocates proceeded with their proposals. Their goal was to make the first two floors of the 4-story building smoke free, with the third and fourth floor having a phase-in agreement as current smokers move or quit smoking. YoCo-HOP embarked upon a youth-led education and outreach campaign to inform Maria Alicia residents about the advantages of adopting a smoke free policy. Two community meetings were held with tenants. The first one in May 2003 was a general meeting about the proposals, while the second meeting in June especially targeted Spanish-speaking residents with bilingual materials, translation services, and a slideshow.

In their meetings with tenants, the youth advocates emphasized three points favoring adoption of a smoke free policy:- Making rental units smoke free saves money by reducing the damage smoke causes to the property and reduces tenants’ risk of fire damage which can lower the cost of insurance.

- It is legal for landlords to make rental units smoke free. Smokers are not a protected class under anti-discrimination laws and smoking is not a constitutional right.

- Nonsmokers have legal justification to have smoke free units. Disabled individuals, including those with breathing problems, have special rights under state and federal fair housing laws

Maria Alicia residents representing all 20 units and 81 residents adopted the strongest policy that was proposed, making all floors smoke free, including living units, with phase-in for the 3rd and 4th floor, by signing the Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement. In June 2003, YoCo-HOP and Maria Alicia residents celebrated the passage of a voluntary smoke free living environment community agreement to ban smoking in most of the building – the first of its kind in San Francisco.

Working through their tenant association, tenants in every unit voluntarily agreed to designate the common areas and residential floors as smoke free to be implemented in phases with the goal of making the building a completely smoke free environment. For now, the agreement will be enforced solely through tenant mutual accountability. Participants in the process don’t foresee enforcement problems because there has been so much education among tenants, but if there is a problem, tenants can remind each other of the agreement, or raise the issue at a tenant meeting.

The Press ConferenceIn July 2003, YoCo-HOP marked this unprecedented event in public housing with a press conference, inviting local newspapers, television, and radio stations to acknowledge the achievement of the tenants and the youth. El Reportero newspaper, El Tecolote newspaper, KCBS Radio, KGO Radio, Channel 7 news, Telemundo and Univision attended the press conference. Supervisor Chris Daly presented YoCo-HOP youth advocates with certificates of recognition for their hard work and commitment to tobacco control efforts and community health. He also commended the residents of Maria Alicia Apartments for their participation in the agreement.

Speaking on behalf of the American Lung Association, Michelle Rivero applauded the agreement. “We expect a wave of similar agreements to be passed in the next year and are working with the residents in six other San Francisco apartment building who want to formulate their own,” she said. “The Maria Alicia agreement marks the launching of an exciting new trend in tobacco control.”

Passing a Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement at Juan Pifarre Plaza

At the conclusion of the first two-year funding period, TFP contractors that had demonstrated significant progress towards their goals were provided with six months of additional funding. MHDC was selected as one of those providers. The objectives for the extension grant were to:

- Work with Juan Pifarre Plaza residents to adopt an agreement similar to the Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement initiated at Maria Alicia Apartments, and

- Expand the existing Maria Alicia Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement to be included in the residential lease agreement.

“It makes me proud that residents were so supportive and that our building is the first in San Francisco to break new ground in tobacco control. That it was youth that made it happen is even better!”

Juanita, 16 years old, YoCo-HOP advocate and Maria Alicia resident

In January 2004, the program was restructured to accommodate the youth advocates into the six-month extension. The youth group for the extension period was reduced from eight to five – and four of them lived at Juan Pifarre Plaza. In February, the youth advocates were trained on the new workplan and on the Community Action Model. As part of the diagnosis development, the youth discussed different approaches they would take with JPP residents about the smoke-free housing surveys and possible proposals. The youth concluded their JPP neighbors would be supportive of their proposals – even though they knew some smokers lived at JPP – because they were mostly community minded and active in the building.

In March, YoCo-HOP conducted a presentation at Juan Pifarre Plaza (JPP) to tenants on the tenant coordinating committee describing their success at Maria Alicia Apartments with passage of the first Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement.

In April, the youth advocates conducted their secondhand smoke and smoke-free policy surveys of JPP tenants to assess their interest and willingness to adopt smoke free housing policies. Out of 30 units, 28 responded to the surveys. The majority supported policies restricting smoking in common outdoor areas (52%) and policies restricting smoking in common indoor areas (82%). The youth decided that since common indoor smoke free policies already were in place, the proposals that would have the greatest effect would be smoke-free indoor balconies and phase-in units, and smoke-free common areas with a designated smoking area at the farthest point from the building in the garden.

“I live in Juan Pifarre Plaza, which is one of Mission Housing’s buildings. What motivates me to work in YoCo-HOP is wanting to make a difference in the community and to be a leader not a follower.”

Margarita, 15 years old 15 years old, Burton High School

In May, the youth advocates presented the survey results and the various smoke-free living environment proposals to JPP tenants. After a discussion with tenants about the enforceability of the policy, the youth decided to return and present to a larger group of tenants. The third and final presentation occurred in early June. By then, Caritas Management Corporation had adopted statewide legislation banning smoking within 20 feet of entryway and windows. The tenants agreed that the next best move would be to add an indoor agreement encouraging tenants not to smoke in their units. The residents voted on the various proposals and, after a long discussion about the practicality of the smoke-free units, decided to adopt a smoke-free living environment community proposal to include indoor common areas and phase-in smoke-free units.

On July 29, 2004, a community celebration and press conference were held at Juan Pifarre Plaza to celebrate the adoption of the Smoke Free Living Environment Community Agreement at JPP. The celebration also acknowledged and honored achievements of similar TFP projects working throughout San Francisco.

YoCo-HOP youth advocates also conducted a presentation at the Mission Housing Annual Summer Getaway, where they spoke to nearly 300 people about the agreements passed at Maria Alicia Apartments and Juan Pifarre Plaza. This gave the youth a forum to talk about their accomplishments and connect with other people interested in adopting similar policies in their buildings and apartments.

Proposed HUD Amendment

In its previous research, YoCo-HOP had found no specific federal or state statutes, regulations, or case law that would prohibit a local public agency from instituting a “no smoking” policy in publicly subsidized buildings. In November 2003, YoCo-HOP prepared and submitted a model position paper to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), the federal agency responsible for overseeing public housing. The paper proposes that HUD amend its policy to specifically allow owners and sponsors of publicly subsidized housing and local property management companies to implement smoke-free building policies. In the ensuing months, however, YoCo-HOP encountered barriers trying to locate the appropriate HUD official to address this issue. In the absence of a specific HUD policy or before the matter has been tested in court, Caritas Management Corporation has been reluctant to include smoke free policies into the Rental Lease Agreement at Maria Alicia. Caritas, however, has decided to pilot test the inclusion of smoke free policies in the Rental Lease Agreement at the early stages of a building development process at one of their buildings which is under construction.

- Outcomes: YoCo-HOP youth advocates were successful in meeting their project goals.

- Smoke-free Living Environment Community Agreements were adopted by tenants at two MHDC buildings: Maria Alicia Apartments and Juan Pifarre Plaza.

- Advocates researched, prepared, and submitted a model position paper to HUD requesting that HUD support the implementation of smoke-free policies in publicly subsidized housing.

- Challenges: “We developed a group of young leaders that we feel positive about and know that they will be a positive influence in their communities no matter what they end up doing in life. To achieve policies and victories, changing and forming policies and being on the forefront of tobacco control is aaccomplishment. Having the first housing project to become a smoke free environment … then having it recognized by the Board of Supervisors and seeing the kids at n press conferences and recognition by policymaker. We’ve had high expectations, but it takes a journey to get there.”

MHDC Director of Resident Programs

Low survey response

Obtaining an adequate response rate was a challenge. Some residents were not at home and others did not want to participate. Most residents were working, some during the day, others at night, so there was no good time to find most people at home. The youth often returned a second or third time to try and catch people.

Organizing tenants

Residents were less willing to attend meetings when the agenda was not related to regular building issues. YoCo-HOP advocates conducted a lot of door-to-door outreach and even called tenants ahead of time to remind them about meetings. The youth found that getting on the agenda of regular resident meetings was more effective than scheduling separate meetings.

Working with bureaucratic systems

Caritas Management Corporation was reluctant to adopt policies that they worried could expose them to legal action. HUD’s first response – verbally communicated – was that management companies and owners of HUD-subsidized housing had the right to implement any policies as long as they were in compliance with the Fair Housing Act and did not violate the rights of tenants to fully enjoy their unit. This was corroborated in a memo from HUD, as follows.

“There are no statutory provisions or regulations governing smoking in HUD-assisted units. There are no provisions prohibiting the owners of HUD-assisted properties from designating certain units for smokers or nonsmokers. HUD-assisted projects are required to comply with applicable state and local laws, which would include any such laws governing smoking in residential units. Restrictions on smoking would normally be found in house rules, and owners of HUD-assisted housing are free to adopt reasonable rules that must be related to the safety and habitability of the building and comfort of the tenants. House rules must not be applied in such a way as to violate the Act or other HUD requirements.”

William Himpler, Deputy Assistant Secretary for Congressional Relations, HUD.

HUD’s unwillingness to take a formal position and provide more explicit language in a policy allowing property management companies to implement smoke-free building policies exacerbates Caritas’ reluctance to risk testing the types of activities in which tenants can engage in the privacy of their own apartments and to include the policy adopted by the tenants in their lease.

However, as stated above, Caritas Management Corporation did decide to pilot test the inclusion of smoke free policies in the Rental Lease Agreement at the early stages of a building development process at one of their buildings under construction.

Landlord-tenant struggles

MHDC and Caritas buildings were experiencing a large tenant outcry over many recent changes to their lease agreements. For some tenants, the proposal for smoke-free housing was yet another example of how low-income people are disproportionately burdened by heavy regulation. YoCo-HOP advocates, however, were able to demonstrate that the smoke-free policies differed from other regulations in that it was a tenant, not management driven change for the building and community. Unlike other lease amendments, tenants had an opportunity to freely choose smoke-free policies that would work for them.

- Lessons Learned: Recruiting and Retaining Youth Advocates

Recruiting youth from within MHDC buildings provided opportunities for youth to meet and work with peers within their community, and was seen as a form of community building. Successful retention of the youth advocates was in large part due to the combination of stipend and incentives. Secondly, keeping youth involved in tobacco work over the years has given them a sense of ownership and cohesiveness over the work – that this is their project. Another factor contributing to successful retention of youth has been the integration of issues important to youth in the Mission District of San Francisco with tobacco control work globally and framing tobacco control work as empowering youth fighting the targeting of their communities by tobacco companies.

Other factors that contributed to high retention rates include:- Participation and inclusion of parents through meetings, phone conversations, and regular updates.

- The feeling of group responsibility.

- The desire to see the project through to its conclusion.

- The involvement of tenant coordinator who see the youth in MHDC family buildings on a daily basis

- The formation of close relationships with youth and families based on trust and consistency.

Group trips, exposures to new and different experiences, and opportunities to travel also kept the youth advocates interested and engaged:

- Two YoCo-HOP youth advocates and the Program Coordinator attended the Latino Priorities Population Tobacco Control Conference in Los Angeles in October 2003. Staff and youth were co-presenters for a conference panel/workshop on Smoke-Free Live, Work and Play Areas. They described the Agreement they had facilitated at Maria Alicia Apartments and the significance of this achievement in affordable and public housing developments.

- YoCo-HOP youth also attended the Youth Leadership Institutes Youth Summit and attended six workshops, including How to Avoid High Risk Situations, How to Start a Tobacco Cessation Program, and How to Work with the Media.

Getting management involved sooner

The issue of when to get management involved presented a dilemma to the project. On the one hand, in retrospect, building management should have been approached earlier to get their buy-in. That way, according to the Youth Coordinator, “They would have been part of the process instead of another step in the process.” On the other hand, the project did not want to tell management in advance about activities such as the tenant survey because YoCo-HOP wanted to be seen as apart from rather than related to management. While that strategy ultimately worked to the project’s advantage with the tenants, they were more disadvantaged with management who was upset that the project had gone behind their back.Working for policy change

The youth experienced how difficult it can be trying to work with a government agency. “These agencies are like pillars,” said the Youth Coordinator. “It felt like we were taking on giants.” The youth learned that bureaucracies generally don’t change without continuous pressure. “You have to be persistent and clear about what you want, otherwise it doesn’t get addressed,” the Youth Coordinator observed.

The youth advocates learned that worked to change policies resulting in long-term sustainable change takes time, patience, willingness to compromise, and persistence in the face of seeming bureaucratic immobility. Despite moments of low morale among the advocates, when everything seemed completely bogged down, the difficulty of the process gave the youth many new skills. They became strong public speakers. They are impassioned about their work, thus becoming strong advocates. They learned that to be effective they needed to be organized and have their points well organized, whether making presentations before tenants or policy makers. They also learned not to let roadblocks discourage them, to be flexible and willing to work out a compromise, and to be creative around finding solutions. Finally, the youth learned that it takes great leadership to take on policies and changes that have never before been attempted. - Methods: This case study was developed using the following resources:

- Progress reports submitted by MHDC

- Pre/post skills inventories administered by evaluator to Envision Youth advocates

- Project materials (e.g., flyers, announcements, etc.)

- Media clippings

- Staff interviews with Alexandra Hernandez, MHDC Youth Program Coordinator, and Eric Quesada, MHDC Director of Resident Programs

- Interview with youth advocate

- Consultation with San Francisco Tobacco Free Project staff

- Credits:

Prepared by Polaris Research & Development Diane F. Reed

For the San Francisco Department of Public Health Tobacco Free Project

August, 2004

- Download: case study

Download the case study here.

Smoke-Free Public Housing (2004)

Mission Housing Development Corporation

An estimated 200,000 to 1,000,000 asthmatic children have their condition worsened by exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.