- Introduction: Addressing the disparity of tobacco influences in San Francisco

In 2014, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously passed a policy that caps the number of retail outlets that can sell tobacco in San Francisco. The policy was the result of a six-year advocacy effort led by the Youth Leadership Institute (YLI) to reduce the overconcentration of tobacco retail outlets in low income neighborhoods and neighborhoods of color. For over 25 years, YLI has served as an innovative leader in the field of youth development providing support, training, and research for community-based youth initiatives that support community-level and national policy change. Supported with funding and technical assistance from the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project, YLI engaged and trained dozens of young residents from these neighborhoods to assess the problem, gather support from stakeholders, and ultimately pass the policy.

The resulting San Francisco Tobacco Retail Density Policy aims to cut the number of tobacco outlets in San Francisco by half. This case study describes this policy in San Francisco, examines the key strategies and lessons learned in developing a retail density policy, and explores the early impact of the policy in the first year of implementation.

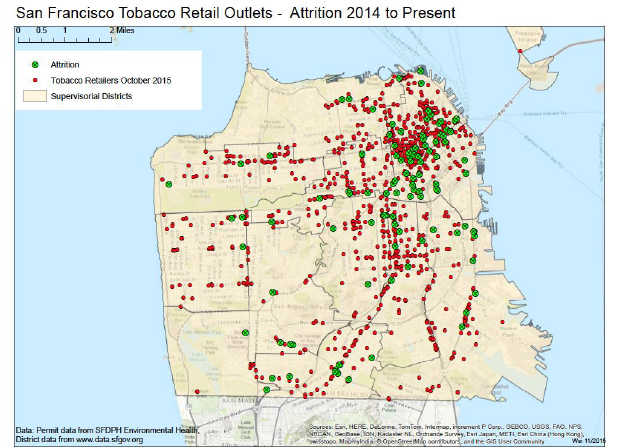

San Francisco’s Tobacco Retail Density Policy (hereafter, referred to as the Density Policy) is an unprecedented effort by a local government to reduce the number of outlets that hold a permit to sell tobacco products. In San Francisco, stores, bars, restaurants and other retail can obtain a tobacco sales permit. The Density Policy caps the number of tobacco sales permits in each of the City’s 11 Supervisorial Districts at 45, limiting the citywide total to 495. With approximately 1,001 outlets licensed to sell tobacco at the time of its passage, this policy will cut in half the number of licensed outlets. The Density Policy does not revoke permits from those outlets that are already licensed to sell tobacco. Rather, it relies on the attrition of stores with permits when new permit applications are denied based on the rules and regulations stipulated in the policy. The Density Policy also restricts retailers from selling tobacco near schools and limits the concentration of outlets on the same block.

- The Community Action Model: Achieving health equity through environmental change

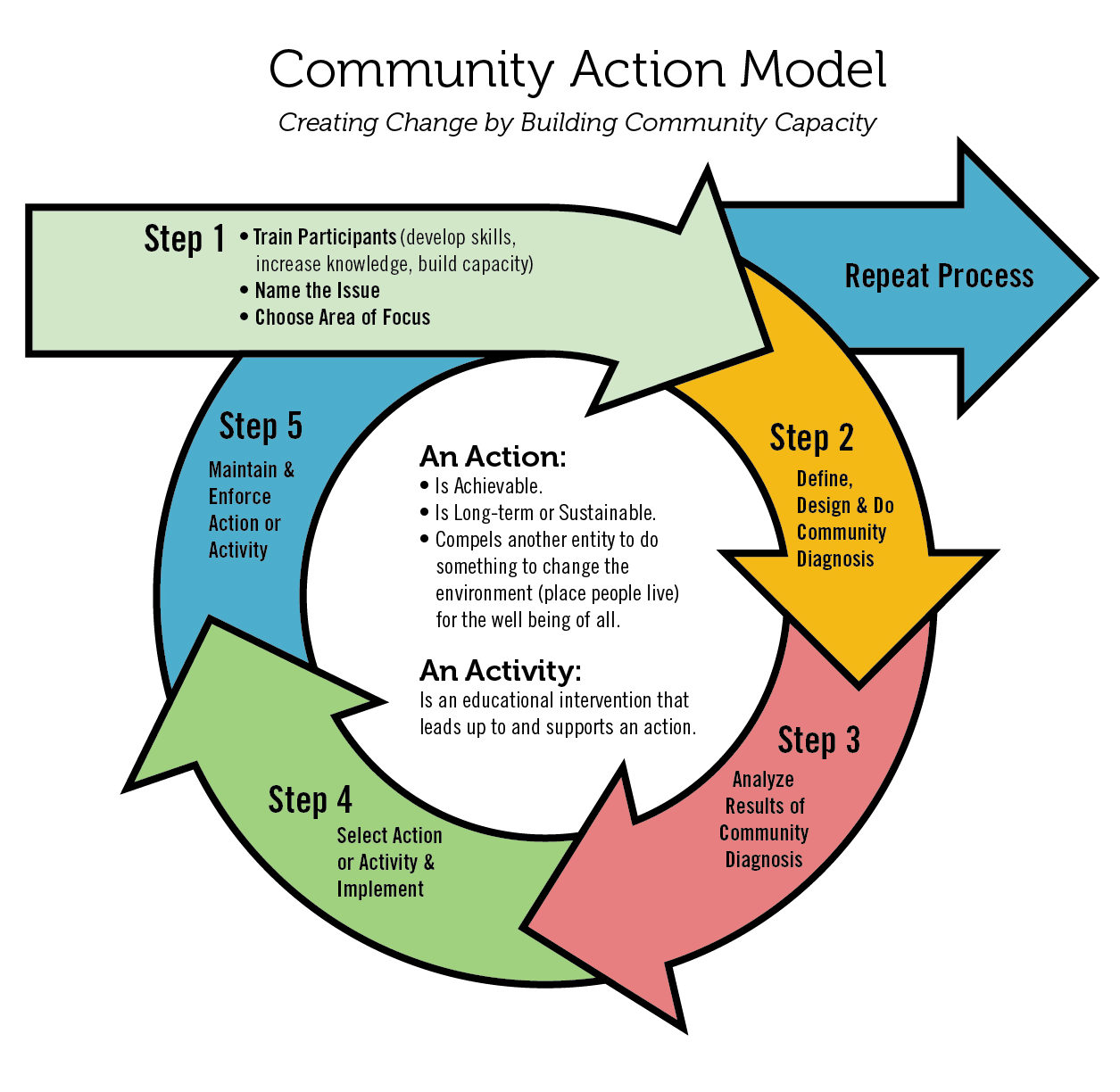

The San Francisco Tobacco Retail Density Policy was the result of six years of research and action from the Youth Leadership Institute. Since 2008, the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project—a project of the San Francisco Department of Public Health—has provided funding and technical assistance to the Youth Leadership Institute to build the capacity of young people to address tobacco control through policy change using the Community Action Model process (CAM). Conducted over a period of two and a half years, the CAM provides a comprehensive five-step framework to train advocates (step 1) to diagnose and research a tobacco control issue in their community (steps 2 and 3) and to design an action—usually a new policy or enforcements of an existing policy—to address that issue (steps 4 and 5). The Tobacco-Free Project provides training, resources, and one-on-one technical assistance to support community-based organizations that are implementing the CAM process.

Defining the Problem

Public health practitioners are exploring novel ways to improve the retail environment to support community health. In dense urban neighborhoods, retail stores often feature signs that promote tobacco products and pricing, streets are littered with cigarette butts, and smoke wafts into apartment buildings where people live. Retailers licensed to sell tobacco are rife with advertisements paid for by tobacco companies and provide easy access to purchase tobacco and other unhealthy products.

Research has linked the prevalence of tobacco outlets in a neighborhood to increased smoking rates. People living in neighborhoods with high densities of tobacco retailers are also more likely to be diagnosed with or die from tobacco-related diseases. The prevalence of these outlets normalizes tobacco use, and increases the frequency with which people are exposed to tobacco. The influence of in-store marketing of tobacco products further normalizes smoking in communities. The National Institutes of Health has found that increased exposure to tobacco advertisements causes youth to start smoking. In addition to affecting youth, in-store tobacco ads have also been found to cue cravings and undermine people’s efforts to quit smoking. Reducing the number of outlets that sell tobacco—and therefore the number of stores that display tobacco advertising and promotions—is a harm reduction strategy for public health practitioners working to promote smoke-free communities.

YLI’s Tobacco Use Reduction Force (TURF)

To implement the Community Action Model process (see inset on page 3), the Youth Leadership Institute recruited over a dozen youth advocates to research tobacco control issues in their community. Alarmed by their research and drawing on their own personal experiences in their neighborhoods, the youth advocates selected the issue of tobacco retailer density as an issue that they wanted to explore. This team of youth advocates was dubbed TURF—or the Tobacco Use Reduction Force. TURF embarked on the Diagnosis and Analysis phases of the CAM process through observations, mapping, interviews, and public opinion surveys.

Observations & Mapping: TURF advocates sought to understand and diagnose the scope of the problem in San Francisco. Advocates conducted community-walking tours to observe retail stores in different neighborhoods and to interview community members about their perceptions of the retail environment. The youth advocates started to take notice of differences in the number of retail stores in low-income neighborhoods when compared to higher income neighborhoods. Retrieving a list of businesses with tobacco retail licenses, advocates mapped the locations of these outlets and found that tobacco outlets (stores, bars, restaurants, tobacco shops and others) were distributed inequitably throughout the city. The six supervisorial districts in San Francisco with the highest number of tobacco retailers were also the districts with the lowest median household incomes. For example, District 2 has a median household income of $105,509 and 56 tobacco permits, while District 6—where the median income is 2.5 times lower at $37,431—has 3 times as many tobacco permits (180).

The maps also showed that communities of color and young people were exposed to higher numbers of tobacco retail outlets. Residents of color live in the neighborhoods with the highest retail density, exposing their communities to tobacco products more than white people who tend to reside in the lowest density districts. In addition, nearly 60% of tobacco outlets in San Francisco were within 1,000 feet of schools—which research has found to be an indicator of whether youth will start smoking. The problem was clear: young people, low-income residents, and people of color were being disproportionately exposed to the harms associated with easy access to tobacco.

Interviews: TURF advocates also interviewed city and county stakeholders, policymakers, and retailers to better understand their perspectives and to inform policy development. Advocates found that the businesses were able to easily access tobacco retail licenses, and most were able to keep them even when they were caught illegally selling tobacco to minors. When a retailer sold tobacco products to minors, Environmental Health would take punitive measures against the store by temporarily suspending their license. However, the average length of time for suspended licenses was shorter than the minimum amount stated in the rules and regulations, and the appeals process made it unlikely that any retailers would have their license permanently suspended except for in extreme circumstances. The existing policy failed to adequately regulate retailers in a manner that would effectively prevent youth access to tobacco—a major public health concern for decision makers and community members in San Francisco.

Public Opinion Surveys: To better understand community concerns, advocates conducted public opinion surveys of a representative sample of San Francisco residents in 2009 and 2012. In the 2012 survey, 88% of residents agreed that too many stores selling cigarettes is bad for their communities health.9 In addition, 78% believed that one store selling tobacco products on every block was too many and 87% supported a policy to reduce the number of tobacco products available in neighborhoods.10 TURF advocates drafted a policy proposal, and pointed to the survey data to indicate the San Francisco community’s support in their conversations with elected officials and other potential allies.

- Strategies for Passing a Retail Density Policy: How to bring about change

A Brief History of Tobacco Retail Density Policy Advocacy

The first attempt to pass a Tobacco Retail Density Policy in San Francisco was in 2009. The Youth Leadership Institute (YLI) received its first CAM grant from the Tobacco-Free Project and convened its first group of TURF youth advocates. TURF advocates researched tobacco retailer licensing requirements, accessed permit and community data, gathered support from Supervisors, and drafted a policy proposal. A Supervisor agreed to sponsor the policy, but the Mayor introduced a conflicting policy on the same issue at the same time. The conflicting policies split political support for the bill—and combined with strong opposition from the business community—the bill ultimately failed to pass. Despite its failure, this first attempt succeeded at educating policymakers and the broader public about tobacco retail density as an equity problem.

In 2011, with a new CAM grant, YLI convened a new group of TURF advocates to restart the effort to pass a Tobacco Retail Density Policy. Advocates refreshed the data from 2009 and built alliances with policymakers, the business community, and other community and economic development-focused organizations. TURF gathered 39 organizational endorsements and commanded media attention. After extensive negotiations with a key stakeholder in the business community—the Arab American Grocers Association (AAGA)—Supervisor Eric Mar agreed to sponsor the bill in 2013. The bill was quickly considered and passed through committee after nearly 30 youth advocates, AAGA and community members testified in support of the bill. The policy was unanimously approved by the Board of Supervisors in December 2014, and went into effect on January 18, 2015.

San Francisco’s Tobacco Retail Density Policy represents a unique and comprehensive effort to reduce the number of stores that sell tobacco products. San Francisco has the most comprehensive policy limiting the number of tobacco retailers in the United States. While many stakeholders in San Francisco shared the equity concerns raised by advocates, it took six years to pass this policy solution. Advocates faced several key challenges that they had to overcome to pass a strong policy. How do you limit the number of tobacco retailers? How do you build support among small businesses that are affected by the policy? How do you build political support? This section describes the challenges and innovations that advocates faced in San Francisco and highlights the lessons learned that other communities could apply in their efforts to reduce tobacco retail density.

How do you limit the number of tobacco retailers?

The foundation of the Density Policy relies on the Tobacco Retailer Licensing (TRL) requirements in San Francisco. The TRL requires retailers to hold a permit to sell tobacco. While the state of California requires all retailers to have a license to sell, some cities in California—such as San Francisco—have opted to require stores to also apply for a local permit. The State of California and local governments use the TRL to enforce tobacco control laws, including tobacco taxes, sales to minors, and other local point-of-sale laws.

Before the Density Policy, there were no limits on the number or location of tobacco retailers in San Francisco. Most retail stores that wished to sell tobacco products could apply to receive a tobacco retailer license in San Francisco. Licenses were generally approved for most establishments, with a few notable exceptions. In extreme cases, licenses would be denied if a retailer was not following all applicable laws and regulations related with the sale of tobacco products.

San Francisco’s effort to use the TRL to reduce the density of tobacco retail environments is the most comprehensive and far-reaching local effort to limit the number of businesses that can sell tobacco and other tobacco products. First, the TRL creates an enforcement mechanism that has measurable consequences on the number of outlets selling tobacco in a jurisdiction. The cap per district was decided strategically to lower the density of tobacco retailer outlets to the lowest number of stores that currently existed in a district. When advocates mapped the number of retailers per district and found that District 7 had the fewest permits at 37, they decided to set the cap per district just slightly above that minimum at 45. In areas such as District 6 and District 4 that currently have 180 licenses, this cap will make a considerable difference in number of tobacco outlets. Second, in 2014, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors approved a policy that requires stores that only sell electronic cigarettes (i.e. “vape shops”) to also hold a tobacco sales permit. As a result, the Density Policy also stymies the availability and future growth of these increasingly popular products and retailers.

Jurisdictions looking to reduce exposure to advertising and youth access to tobacco may learn from the elements of San Francisco’s retail density policy by redefining the conditions for approval of retailer licenses. Other options could include restricting the number of stores on one block, restricting the locations of stores, or restricting the types of stores that could carry licenses. Focusing on the conditions for approving retailer licenses as a strategy to limit tobacco advertising allows jurisdictions to avoid challenges by the Tobacco industry and the First Amendment law. Jurisdictions without TRLs may consider passing one to understand the number of outlets in their communities and enforce policies that protect youth from accessing tobacco products. Given that a variety of retailers sell tobacco, jurisdictions may consider categorizing licenses by the type of tobacco sold to further understand where their community accesses tobacco products.

How do you build support among small businesses?

Most businesses with tobacco retailer licenses in San Francisco are small businesses—“mom and pop” shops, corner stores, or small groceries, usually owned by a sole proprietor. Advocates conducted interviews with these retailers, who shared that up to 30% of their sales and between 8-10% of their profits are from selling tobacco products. Because of their reliance on tobacco sales as a core part of their business model, retailers were strongly opposed to the Density Policy. Small retailers were feeling the pressures of increased regulations in San Francisco, as well as increased competition from the growth in new big box or chain retail stores in San Francisco. Associations representing these retailers—most notably, the Arab American Grocers Association (AAGA)—had successfully organized against the Density Policy when it was first being considered in 2009 and they were poised to do the same thing in 2013.

However, in 2013, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors adopted the Healthy Retail San Francisco ordinance which provides resources to help corner stores shift their business model towards a small grocer that offers fresh and healthy affordable food. Because of the benefits it provided businesses, the Healthy Retail San Francisco program created the opportunity to find common ground with the AAGA and identify a viable density policy solution that could be supported by all stakeholders. TURF advocates, legislative aides from the sponsoring Supervisor’s office, staff from the Tobacco-Free Project, and the AAGA started a working group to discuss the various elements of the formula to reduce tobacco permit density. The working group met at least 6 times between July and December of 2014 at local restaurants owned by AAGA members. The working group created an opportunity for all stakeholders to share their concerns, needs, and priorities in crafting a policy that both protected community health and supported the small business community.

In these meetings, the AAGA educated city and community stakeholders about the economic pressures facing their businesses, as well as the value of these corner stores to Arab families in San Francisco. Many Arab families were sensitive to any decisions that would make it difficult to sell their business because they were relying on the sale of the store as their retirement plan. This key insight into the retailer experience, concerns, and needs created an important foundation for negotiations on the specifics of the policy.

The working group also allowed City agency staffers to educate retailers about the tobacco retailer license. Retailers believed that the TRL was transferable at the time of sale of the business, and that restricting the ability to sell their tobacco license would devalue their business. Tobacco-Free Project staff explained that the TRL cannot be sold, and that all new business owners must apply for a new tobacco retail license—a surprise to retailers.

However, advocates and city stakeholders wanted to limit the economic damage to long-time San Francisco business owners who were close to retiring or selling their business. The proposed policy was amended to allow a one-time permit to be made available to a new buyer if the previous storeowner had been in business with a tobacco permit for at least 5 years. Additional exceptions were added to the tobacco permit density formula to address the small business concerns.

The collaboration with AAGA allowed retailers to better understand the policy concern, participate in crafting the policy change, and prepare appropriately for the policy’s impact. As a result of these negotiations, the AAGA endorsed the policy and their organizer testified in support of the bill in front of the Board of Supervisors. Demonstrating retailer support for the policy was a major deciding factor for many Supervisors, and is one of the key contributors to the success of the policy in 2013.

How do you build political support?

The Density Policy was the result of six years of data collection, organizing, messaging, and negotiations with key stakeholders. Initially, advocates were faced with strong retailer opposition and Supervisors concerned with hurting small businesses during and after the recession. Advocates learned many lessons during the organizing process that eventually contributed to the success of the Density Policy campaign, and that can help inform future policymaking efforts in San Francisco and in other jurisdictions.

First, the Community Action Model (CAM) provides a framework for building community capacity to achieve political support for progressive tobacco control policies. CAM creates an opportunity for community members to drive policymaking and for stakeholders to hear community priorities and concerns. The stories and perspectives that young people brought to meetings, hearings, and events at corner stores were essential at several key points in the policy process, including influencing Supervisor Eric Mar to serve as a sponsor on the bill, demonstrating legitimate youth support for the policy in retailer negotiations, and getting the timely recommendation of the Neighborhood Services & Safety Committee to pass the bill on for consideration in front of the Board of Supervisors. Youth advocates were also able to draw attention from the media, which increased coverage on the issue—and garnered the attention of Supervisors.

Second, the CAM model allowed TURF advocates to rethink the diagnosis of the problem and gather additional support from key stakeholders over the six-year policy period. A TURF Advisory Board was created in 2012, where advisors from labor and community groups provided strategic direction on messaging and talking points, potential endorsements, public education and media campaigns, and other organizing strategies. Advocates reviewed organizational endorsements from the failed Density Policy effort in 2009, and identified that community and economic development groups were missing from the endorsement list. Advocates were able to gain over 39 organizational endorsements from a broad array of organizations including community-based and youth organizations, health and policy organizations, community and economic development organizations, businesses, and commissions and coalitions including the San Francisco Health Commission and the San Francisco Youth Commission. The endorsements of these Commissions and of business-minded organizations—especially the AAGA—built political will among several Supervisors who advocates had been unable to move.

Finally, advocates worked with economic development, zoning, and environmental health staffers at the City and County of San Francisco who would be responsible for enforcing these policies. Advocates tapped into their knowledge of city policies, regulations, and priorities (from the Mayor’s Office, for example) and used this information to craft a realistic and enforceable policy. Building trusting relationships and alliances with these stakeholders is an important strategy for community health advocates and coalitions who are working to reduce tobacco retailer density in their jurisdictions.

- Lessons Learned from Enforcing a Tobacco Retail Density Policy: Passing the law was only the first step

Regulations & Public Education

San Francisco’s Tobacco Retail Density Policy went into effect on January 18, 2015. Once the policy became law, Environmental Health defined the regulations that would ensure compliance with the law under Article 19H of the San Francisco Health Code. While some specific conditions were covered in the legislation, there were many individual circumstances that arose immediately. For example, for people who were in escrow to purchase a retail store before the effective date, the regulations had to clarify whether or not those owners would be eligible under the one-time exception clauses. The regulations also had to clarify what happened to eligibility of a tobacco retail license under the one-time exception in the case of a death, marriage, or divorce of the business owner. As these circumstances appeared in new permit applications, clearer regulations had to be developed to ensure consistency across cases. For example, further definitions were included in the regulations to address different types of ownership of businesses.

Although some retailer associations—most notably the AAGA—were engaged in the policy development process, many individual retailers were not aware of the new law. Retailers started to receive notices that their applications to sell tobacco were being denied. Previously, licenses were only denied if fraudulent information was provided or if the business had repeatedly sold tobacco products to minors. Many retailers were confused and outraged. Environmental Health and the Tobacco-Free Project decided to engage in a widespread outreach effort to educate retailers about the new law. They made presentations in front of the Small Business Commission and the Board of Appeals. They sent mailers to all retailers with a tobacco license to explain the new law.

Environmental Health also conducted in-person site visits to all 972 stores to educate them about the new law and provide them with a specialized letter that described whether or not a buyer of their store would be able to get a permit according to the new rules and regulations. This public education effort helps support the business community with relevant information that can inform their future plans, and ensure a slow and steady attrition of tobacco retailer licenses.

Year 1 Outcomes

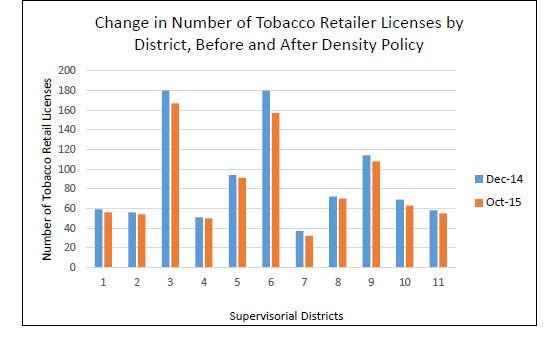

San Francisco projects that it will take 10 to 15 years for the number of tobacco retail licenses to meet the 45 cap per district. However, the impact of the policy on the number of licenses across the City and in each District is already noticeable in the data. The number of tobacco retailer licenses in San Francisco decreased by 8% in the first 10 months since the Density Policy went into effect. All Supervisorial Districts have seen decreases in the number of tobacco retailer licenses. The Districts with the highest number of retailer licenses before the policy went into effect have seen the greatest declines. District 6 has lost 13% of its tobacco retailer licenses in the same time period.

- Conclusions: Final thoughts

Fourteen percent of San Francisco’s residents smoke cigarettes. One in three California youth—37%—have smoked an entire cigarette by age 14. The high number of tobacco retailers in urban neighborhoods contributes to these high smoking rates for both adults and youth. San Francisco’s Tobacco Retailer Density Policy sets a cap on the number of tobacco retailers that will drastically reduce the number of outlets where community members can access or be exposed to tobacco. In addition to reducing harm for the entire population, this policy protects low income communities and communities of color that have disproportionately high numbers of tobacco retailers in their neighborhoods, as well as disproportionately higher smoking rates. Lessons learned and early outcomes from San Francisco’s Density Policy can inform efforts to enact similar protections in other jurisdictions.

- Download: Case study

Download case study here

- Past: Case studies

Reducing Tobacco Retail Density in San Francisco (2016)

Youth Leadership Institute: Tobacco Use Reduction Force

"San Francisco Tobacco Retail Density Policy aims to cut the number of tobacco outlets in San Francisco by half"