- Introduction: The Tenderloin is one of the most at need neighborhoods in the City

The Tenderloin is a complex neighborhood. Located between the upscale Union Square shopping district to the northeast and the Civic Center office district to the southwest, this dense area is not only characterized by poverty, homelessness, squalid conditions, crime, liquor stores, and the highest rates of drug crime and prostitution in the City, but is also known for diversity, vibrant theaters, refurbished community parks, international cuisine, and murals. While housing options in the Tenderloin are limited to single-room occupancy hotels, studios and tiny apartments generally ill-suited for families, the area has become home to many thousands of Southeast Asian refugees and immigrants from Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam and to a growing Latino population. Many of these immigrant families are non-English speaking and most have children. Since the early 1980’s, the child population in the Tenderloin has increased from a very few to over 3,500 children.

The Tenderloin has more than its fair share of problems. Children growing up in the neighborhood must navigate some of the roughest streets in San Francisco, often walking past piles of garbage and drunks passed out on the sidewalk, and where public urination is common. Children must learn to resist an environment that promotes rather than prevents choices that can lead to poor health. Among its many problems are tobacco-related ones, including a massive amount of tobacco-related litter in the streets, such as butts, filters and discarded packaging. Cigarette and alcohol advertisements are plastered all over the neighborhood. District 6, which includes the Tenderloin, has 270 outlets, many small corner stores, with permits to sell tobacco, representing 27% of all tobacco outlets in the City. If all permits where distributed equally in SF, there’d be an average of 91 permits per district. The Tenderloin, with 270 tobacco permits, has at least three times more than the average . Cigarettes are often strategically placed next to candy displays, targeting young people. One smoke shop is even located directly across the street from the Tenderloin Children’s Playground. Not surprisingly, a 2006 survey conducted by the Tenderloin-based Vietnamese Youth Development Center revealed that 35% of youth under 18 years old living in the Tenderloin had tried and/or smoked cigarettes and that 29% under 18 years were smoking at least once a month.

A 2009 an audit conducted by the City found that in 2008, San Francisco spent over $24.7 million cleaning up public litter, with cigarette-related waste alone amounting to over $6 million, or about 25% of the City’s annual litter removal costs. In its study of this issue, the Board of Supervisors found that “in addition to the aesthetic degradation that results from litter generally, cigarette litter uniquely damages the environment. The smoked filter and leftover tobacco from smoked cigarette butts contain a variety of toxic organic compounds and heavy metals that can cause toxicity in the marine environment.”

Based on the audit, the Board of Supervisors passed an ordinance in 2009 imposing a 20-cent fee on the sale of every pack of cigarettes sold within.

- Community Action Model: Dealing with the Tobacco Litter issue

In implementing its action, Team LST utilized the Community Action Model (CAM), a process that builds on the strengths or capacity of a community to create change from within and mobilizes community members and agencies to change environmental factors promoting economic and environmental inequalities. CAM steps include:

Train participants to develop skills, increase knowledge and build capacity.

Do a community diagnosis to find the root causes of a community concern or issue and discovering resources to overcome it.

Choose an action to address the issue of concern. The action should be achievable, have the potential for sustainability, and compel change for the wellbeing of all.

Develop/implement an action plan which may include an outreach plan, media advocacy, developing and advocating for a model policy, presentations, and evaluation.

Enforce/maintain the action after it is successfully completed to maintain it over the long term with enforcement by appropriate bodies.City boundaries to help mitigate the cost of cleaning up cigarette-related litter. The ordinance established an Environment Cigarette Litter Abatement Fund to be administered by the city’s Office of the Treasurer & Tax Collector and to fund DPW to clean up cigarette litter from sidewalks and other public spaces, collection and enforcement, public outreach and education, and fee administration. Since the passage and implementation of the ordinance, over $4.5 million in fees has been collected.

Despite the infusion of additional resources now available to clean up cigarette-related litter, the fees collected by the Cigarette Litter Abatement Fund are not officially disbursed proportionally based on the number of cigarette packs in each district. District 6, of which the Tenderloin is a part, accounted for 27%,or5.7 million packs, of the 21.04 million cigarettes sold citywide (since the enactment of the ordinance) and small retail food markets, including corner stores, account for fully half of the primary point-of-purchase for cigarette packs citywide.

Many community-based organizations are working in the Tenderloin to make it a better place to live. Since 1978, the Vietnamese Youth Development Center (VYDC) has been one of them. VYDC, a multi-service youth center located in one of San Francisco’s toughest neighborhoods, offers employment, counseling, leadership development and support to all youth ages 11-24 years old. The organization provides direct assistance to Southeast Asian and neighborhood youth by empowering them and their families to participate actively in the development of their community, and preparing young people to successfully transition into adulthood.Under contract to the San Francisco Tobacco-Free Project (TFP), VYDC convened a group of 11 young high school and college-age advocates ranging from 14 to 20 years old to work on tobacco control issues in the

Tenderloin. The advocates were a diverse group of Vietnamese, Chinese, Pakistani, Eritrean, Filipino, Latino, and African American, and many spoke native languages, including Vietnamese, Chinese, and Tagalog. They called themselves Team Let’s Stop Tobacco, or Team LST.In their initial research, the advocates identified some major tobacco-related problems. First, there is a very large quantity of cigarette litter in the Tenderloin. “When you walk on the street, they’re in every corner, hundreds of butts littered on the ground and curbs,” said the Project Coordinator. Second, there is a high density of corner stores in the neighborhood: three are located on the same corner as the VYDC office. The products sold by these stores the quality and quantity of foods available to families and children in the neighborhood who do not have ready access to larger stores that provide fresher, healthier foods. –There is an oversaturation of tobacco, alcohol, junk foods in the community. Easy access to these products, e.g. chips, soda, cheap malt liquor, etc., and a lack of access to healthy food, create an. unhealthy The advocates also found that many of these corner stores were not following basic city laws that limit outdoor advertising to no more than one-third of storefront windows, that require “No Smoking” signs and the tobacco retail license to be properly posted, and that require litter receptacles/ashtrays to be available and maintained. Team LST advocates undertook an ambitious phase of research and collected compelling data on these issues.

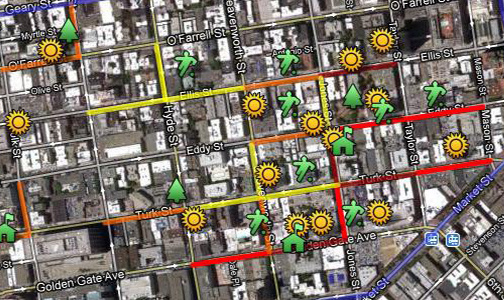

Litter collection. On three consecutive Tuesdays in October 2011, two groups of Team LST advocates collected cigarette butts from sidewalks on randomly selected blocks in the Tenderloin, particularly near schools and community centers. In about 2 hours and 15 minutes (three sessions of 45 minutes each) over the three day period, a total of 2,072 cigarette butts were collected from 24 blocks of sidewalks in the neighborhood. A color-coded rating system was created and data on the number of butts collected from each block was plotted on a Google map. The map (see Figure 1) shows the “hot spots” where butts were found. The advocates also interviewed an official from the Department of Public Works (DPW) and researched the cigarette litter abatement fund to learn more about the ordinance passed in 2009. They then interviewed an official from the City Tax Collector’s Office who provided data on the number of cigarette packs sold by district since passage of the ordinance. The data revealed that District 6 has three times more sales than any other district. The youth wondered why funds were not proportionally spent so that the Tenderloin would get its fair share to clean up the area.The advocates researched and created an educational pamphlet on the environmental and health hazards of cigarettes, including:

- Cigarette butts are toxic waste, and filters can take 10 or more years to decompose.

- Cigarette butts can affect our drinking water, and are toxic to fish and other aquatic life.

- A 2011 fire in the Tenderloin that was caused by a discarded cigarette butt left 65 people homeless.

Corner stores. The youth advocates researched the San Francisco government website for city policies that require businesses to provide ashtrays and litter receptacles. They found that any establishment that sells food or beverages – which includes all corner stores – must provide and maintain a litter receptacle outside each exit of their store. Further, any person who operates a place of employment is required to maintain an ashtray for their employees and for patrons that smoke. The youth visited 46 tobacco retailers in the Tenderloin neighborhood – all of which are classified as “retail food markets with or without food prep” and less than 5,000 square feet (defined by the advocates as “corner stores”) and used a checklist and rating system they had developed to evaluate the stores. “The youth felt that if they got graded in school, the stores should be rated too. Not only is there huge density in the Tenderloin of corner stores, but their quality should be judged,” said the Project Coordinator.

Of the 46 corner stores in the TL, 33 allowed the advocates to survey them. Key findings include violations of city and/or state laws among the 33 surveyed corner stores where almost all the stores were not in compliance with at least one city law:

- 13 (39%) did not visibly display their San Francisco Tobacco Retailer permit, in violation of a citywide Tobacco Retail Licensing Ordinance.

- 28 (85%) did not display “No Smoking. Only at the Curb” signs outside their stores, in violation of a citywide Health Code.

- 10 (30%) did not visibly display their S.T.A.K.E. Act signs, in violation of the statewide Stop Tobacco Access to Kids Enforcement Act.

- 25 (76%) had more than one-third of their outside storefront (windows and doors) covered by any type of advertising, in violation of a citywide policy as well as the statewide Lee Law.

Additional findings include:

- 14 (42%) of corner stores had a litter receptacle outside their store.

- None of the corner stores had an ashtray.

- 7 (21%) had more than 13 advertisements outside the stores.

- 14 (42%) had no fresh fruits or vegetables for sale and much of what they had was wilted or old.

- Only 11 (33%) had 8 or more types of fresh produce available.

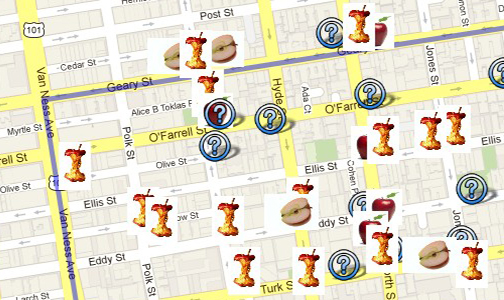

The LST Team advocates inputted the data, created a checklist rating system, scored each checklist and rated each store based on a 6-point “bad apple” scale (e.g., a store received a total of 6 points for complying with city policies already in place, including the Lee Law, posting their Tobacco Retail Permit, posting the “No Smoking” sign outside their store, posting the S.T.A.K.E. Act sign, and maintaining a litter receptacle outside their store). Based on the results of their survey:

- 21 (64%) of the stores were rated as “rotten apples”

- 5 (15%) were rated as “half apples”

- 6 (18%) were rated as “good apples”

The youth leaders then mapped each corner store, using “good apple,” “half apple,” or “rotten apple” as icons for each store based on their rating score .

Team LST advocates collected additional useful information from three focus groups they conducted at different locations in the Tenderloin to explore how youth of various age groups are affected by the density of corner stores in the neighborhood. One focus group was held at the Community Youth Center with 8 high school aged youth 15-17, the second at VDYC with four young adults ages 21-22, and the third at the Tenderloin After School Program with 8 middle school aged youth ages 12-14. Key focus group findings are:

- Most of the younger youth and teen (12-17) focus group participants reported feeling unsafe in the Tenderloin: all felt uncomfortable walking in the neighborhood because of the homeless, loiterers, and drunks harassing people who walk by.

- Most of the older youth (21-22) reported feeling safe as long as they kept to themselves, but said they still “keep their guard up.”

- Participants agreed that the stores “all seem to sell the same unhealthy products” and seemed to understand how this affects the health of the community, even though most participants admitted to purchasing unhealthy products (e.g. chips, candy, soda) at those corner stores. They said they would like to see reasonably priced healthier prepared food (e.g., good sandwiches instead of fried chicken) available at corner stores.

The youth advocates developed a paper survey for Tenderloin community members of all ages. Over the course of two one-hour sessions, the youth surveyed people at the Tenderloin Youth Development Network’s movie night in November 2011, and inside and outside the Tenderloin Recreation Center and at the VYDC in December 2011. A total of 42 surveys were collected. Key survey findings are:

- Younger people shopped at corner stores much more often and purchased convenience snacks like chips and soda.

- Respondents shopped at a corner store on average 2.4 times per week, and nearly half reported having shopped at a corner store that day or the previous day.

- Most respondents thought that the most popular products sold at corner stores are cigarettes, alcohol, and chips/candy; the products respondents most wanted to be available at corner stores are fresh produce, meat, dairy and eggs.

When asked what two things they wanted to see changed at corner stores, the most frequent answers were more healthy foods at reasonable prices, less loitering, less alcohol and cigarettes sold in the community, and having a large grocery store in the Tenderloin.

The advocates also conducted final additional research to learn more about San Francisco’s current Tobacco Retail License Ordinance and a 2011 statewide survey about how California voters feel about tobacco retail density and license revocation issues.

The advocates realized that the wealth of information and data they had collected and the multiple issues going on in the Tenderloin pointed to many different policy options and/or actions that could improve the quality of health for Tenderloin residents, making it difficult for them to choose a specific action to work on in the final year of the project. However, the cigarette litter and rotten apple maps proved to be a turning point in helping the advocates focus on an action.

In the course of reaching out to stakeholders in the Tenderloin, Team LST had approached the North of Market/Tenderloin Community Benefit District (CBD) and presented their findings. Impressed with the research, the CBD referred the youth advocates to two large Tenderloin community organizations – the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation (TNDC) and the Central City SRO Collaborative (working with single room occupancy residents). These stakeholders and the Team LST youth advocates organized a community meeting attended by about 50 residents. After the meeting, one of the residents said, “We don’t have a grocery store and won’t get a full service one for a long time, so instead of blaming the corner stores, let’s use them as an asset. Rather than try to shut them down, let’s work with them and make sure they’re following certain laws and make sure they are a positive force in the community.” As a result of that meeting, the Team LST research and input from the residents, a new coalition was formed – the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition (TLHCSC), which now actively meets twice a month.

Team LST youth realized that even though they were contracted with the SF Tobacco-Free Project, recent experience with groups and coalitions had taught them that in working on tobacco issues in terms of corner stores, they were also confronting an interconnected pattern of tobacco, food, and alcohol problems in the community. This helped them solidify their goal for the next year to work on getting existing laws enforced.

“The youth knew that YLI [another youth group contracted with SFTFP] was working on a citywide policy to reduce tobacco permit density that wouldn’t shut down current stores but would put a cap on the number of future tobacco permits available in high density areas.” the Project Coordinator explained. “They knew that was in the works, so why work on that when we know in our neighborhood there are compliance issues and other things to work on. It happened that way because we had so many community partners and such a big resident voice. It seemed that rather than taking on a big citywide project, this would make more sense for our neighborhood.” The advocates proceeded to take action.On the litter issue: The advocates provided the documented results of their research to the Department of Public Works (DPW) and met with a representative about providing litter receptacles/ashtrays and enforcing existing laws in the Tenderloin. The youth requested that DPW distribute funding from the Cigarette Litter Abatement Fund to districts in proportion to the sales of cigarette packs – and, in particular, because the Tenderloin sells a disproportionate amount of cigarette packs compared to other districts – to make more funding for cleanup services available to the Tenderloin. DPW agreed to try working out a way to get additional funding for a curb side ashtray program to be coordinated with healthy corner store efforts in the Tenderloin in February 2013, and to launch some sort of public outreach or media campaign about using the ashtrays.

On the corner store issue: Team LST advocates approached the Departments of Public Health (DPH) and Environmental Health (EH) to request that the City enforce the law requiring tobacco retail owners to post “No Smoking” signs. The youth wrote a formal email to DPH with a copy to EH, and included a list of the stores not in compliance with the “No Smoking” sign law. EH wrote letters to each store owner on the list informing them that they need to comply with the law.

Team LST followed up by visiting the stores and giving them free “No Smoking” signs. The youth told the store owners, “We’re part of the community and just passing out the signs. We’re doing this for the community, not to get you in trouble.” They found general support among the stores which, after receiving the letter from EH, were happy to accept and post the signs.

The advocates are pleased that, while initially only 15% of the Tenderloin corner stores first surveyed had their “No Smoking” signs up, after their strategy of personally giving signs to the store owners, now 97% of the surveyed corner stores are in compliance with the law. The youth plan to visit the remaining 13 stores that would not talk to them originally and, as a community courtesy, offer free signs to them.

The advocates held a community press conference on December 3, 2012. This event marked a transition point for the advocates. The youth organized a community rally outside one corner store; presented the work they have done, and announced having received a $25,000 grant to launch a new effort with the Tenderloin Healthy Corner Store Coalition. The award – a direct result of Team LST’s two years of researching, surveying and working with corner stores and residents – will be used to sponsor at least one corner store in the Tenderloin and transform it into a healthy corner market carrying affordable, wholesome food choices.

Working on this project provided the advocates some notable lessons, including:

- Focusing on one issue. It was a challenge for the advocates to choose one thing to work on because there are so many important issues needing work in the Tenderloin related to drugs, violence, poverty, etc. It was even more difficult for the youth because they live in the community they were trying to impact (as opposed to groups working on citywide issues). Initially, the youth went in several different directions responding to the many challenges in the community. “They wanted to make an impact,” said the Project Coordinator, “and wanted to do multiple things. It was a little hard to reign in and say we’ll just do one thing.”

- The power of collaboration. Given the many other organizations in the Tenderloin that were trying to do similar work, the youth realized it made no sense to try to do everything themselves when they can collaborate with the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation that has already organized “thousands of residents that are thinking the same thing.” The advocates learned that what they were doing went far beyond being a “youth” issue. “There are a lot of people who want the same thing, so why should we compete with everybody else when we can all work together on it and form a group of different organizations, youth, residents, and even the local mosque was involved,” said the Project Coordinator.

- Download: case study

Download the case study here.

Tobacco Litter in the Tenderloin (2013)

Team Let’s Stop Tobacco: Vietnamese Youth Development Center

35% of youth under 18 years old living in the Tenderloin had tried and/or smoked cigarettes.