- Introduction: What is DSCS?Dolores Street Community Services (DSCS) works to prevent homelessness, create affordable housing, build community, and empower low-income residents of San Francisco. It accomplishes this through providing culturally appropriate neighborhood-based services, education advocacy and community organizing.Dolores Street runs or collaborates five distinct services for the community: they run the Dolores Housing Program, the Richard M. Cohen Residence and Valencia Community Center and they collaborate as part of the Mission SRO Collaborative and the Immigrant Legal & Education Network.

- THE PROBLEM: SRO tenants unable to file complaintsThere are more than 19,000 SRO rooms in San Francisco, about 2,000 of which are in the Mission District. Fire hazards are pervasive in SRO hotels for a variety of reasons, including: aged housing; tenant behaviors, including smoking; and a general lack of knowledge about fire safety and prevention information. Since 1997, a series of fires in San Francisco SRO hotels have resulted in a loss of 650 housing units and approximately 1,000 residents have been displaced.However, SRO tenants did not have an easy and accessible way to file complaints aboutpeople smoking in common areas, secondhand smoke, the lack of smoke detectors, bedbugs or other maintenance issues.

- WHAT THE ADVOCATES ACCOMPLISHED: Successes of DSCSAdvocates worked to make tobacco-related fire safety accessible to Mission District SRO tenants through empowerment and the creation of effective complaint and code enforcement mechanisms. Tenant stabilization is a primary goal of Dolores Street and the SRO collaboratives.In December 2009, the “311” SRO program in San Francisco was established, enabling SRO tenants to file complaints with City departments. In addition, SRO landlords and operators are required to post the availability of the 311 service to tenants.

- THE INTERVENTION MODEL: The Mission SRO Collaborative utilized the Community Action Model (CAM), a process that builds on the strengths or capacity of a community to create change from within and mobilizes community members and agencies to change environmental factors promoting economic and environmental inequalities.

The Community Action Model includes the following steps:

- Train Participants: Community Action Team (CAT) members are recruited and trained to develop skills, increase knowledge and build capacity. The participants will use this knowledge and skills to choose a specific issue or focus and then design and implement an action to address it.

- Do a Community Diagnosis: A community diagnosis is the process of finding the root causes of a community concern or issue and discovering the resources to overcome it.

- Choose an Action: to address the issue of concern. The Action should be: 1) achievable, 2) have the potential for sustainability, and 3) compel a group/agency/organization to change the place they live for the well being of all.

- Develop and Implement an Action Plan: The CAT develops and implements an action plan to achieve their Action which may include an outreach plan, a media advocacy plan, development of a model policy, advocating for a policy, making presentations as well as an evaluation component.

- Enforce and Maintain the Action: After successfully completing the action, the CAT ensures that their efforts will be maintained over the long term and enforced by the appropriate bodies.

- THE STRATEGIES: How DSCS adapted the Community Action Model1. Training Participants

DSCS recruited eight adult advocates. Advocates from DSCS along with advocates from other Tobacco Free Project funded projects participated in a 4 hour joint training on July 16, 2008. The training covered a variety of topics including tobacco as a social justice issue, the global reach of tobacco, the impact of the tobacco industry on communities of color, and how to effectively implement the Community Action Model (CAM).

2. Do a Community Diagnosis

The community organizer and the advocates used research, asset mapping, and surveys in their community diagnosis.Research. The advocates developed a tool to research the existing policies, laws, procedures, and regulations of various code enforcement agencies that may impact tobacco-related fire safety for tenants in SRO hotels, including the SF Fire Department, the Department of Building Inspection, and Department of Public Health. Their research included eight main areas:

- The history of cigarette-related fire prevention policies and laws in non-profit and private SROs in San Francisco;

- The history of cigarette-related fires in SROs during the last 20 years and its impact on SRO tenants;

- Local and national tobacco-related fire prevention policies;

- Current fire department protocol for making a complaint and, if none exists, documenting the current process for filing a complaint;

- How proper code enforcement could have prevented the fires;

- Identifying governmental bodies with both compliance and enforcement responsibilities that oversee fire prevention policies in San Francisco;

- Identifying key leaders on commissions and boards (including the Board of Supervisors, DBI, DPH, SFFD) to which code enforcement agencies are accountable; and

- Identifying the policymaking body most appropriate to adopt the policy, protocol, and/or regulation that allows and empowers SRO hotel tenants to advocate for themselves on issues of tobacco-related fire safety and habitability that might lead to a proposed policy to address cigarette-related fires.

Asset mapping. During a Midwest Academy Strategy community mapping exercise, the advocates identified potential allies and opponents in institutions, agencies, organizations, and associations related to code enforcement and fire prevention in SRO hotels. Meetings were held with St. Peter’s Housing, Central City, Chinatown SRO, Families in SRO Collaborative, Association of Residential Hotel Owners, and others to advocate for support. An asset map of allies and opponents was created, including gatekeepers, challenges, allies, supporters and opponents.

Surveys. Three tools were developed. The first was created to evaluate the effectiveness of existing protocol and track the status of about 20 fire safety-related complaints and habitability complaints that were filed by community-based organizations, advocates, and tenants. The advocates wanted to know how and where past complaints were routed (e.g., what city department was called), and the process that was used for smoking-related complaints, including the lack of smoke detectors. The advocates kept track of the department that was called and conducted weekly check-ins with the appropriate enforcement agency to monitor the complaint process.

Second, the advocates developed a checklist to use in tracking fire code violations in the common areas of SRO hotels, e.g. smoke detectors, sprinkler systems, blocked fire exits, etc. Using the checklist, the advocates surveyed 25 of the 50 SROs in the Mission District for fire-related issues.

Third, the advocates developed and conducted a survey in English and Spanish about tobacco-related fires and secondhand smoke with 163 tenants in 25 SROs to identify habitability issues and collect demographic information. The advocates also completed the fire code checklist at each SRO that was surveyed. The survey results revealed that tenants have real concerns about secondhand smoke exposure and not having smoke detectors. The survey also found that smoking rates among SRO tenants are higher than citywide rates. They also found that less than half of the tenants surveyed had access to a phone, while calls to 311 from pay phones were free. Based on that data, the advocates broadened their diagnosis to include smoking and non-smoking issues (e.g., maintenance issues, lack of smoke detectors, bed bugs, maintenance issues).

3. Choose an Action

Based on the findings from their community diagnosis, the community organizer and advocates decided to advocate for the “311” program in San Francisco to establish an effective complaint, code enforcement, and tenant notification process that would facilitate and streamline the ability of SRO tenants to file complaints with City departments.4. Develop and Implement an Action Plan

The advocates began by exploring the possibility of using “311” program as a resource for SRO tenants to report code enforcement problems and other issues. A meeting was held with representatives from San Francisco’s “311” program – a 24/7, 365 days/year citywide telephone system designed to connect residents, businesses, and visitors with general, non-emergency governmental information and services. Following this contact, the advocates decided to work for two new policies. The first was to expand the “311” program to allow SRO tenants to report problems, and the second was to require signage in all of San Francisco’s SROs explaining this new tenant resource.Phase One. The advocates developed a “311” educational proposal packet that included highlights from the research they had completed, outlined the project’s two policy proposals (e.g., using the “311” system as a way to phone in SRO violation complaints and posting the new resource for tenants), provided background information, and listed endorsements of the proposed policy. The packets were presented to relevant city department staff, other stakeholder agencies, groups, and policymakers to gain support and facilitate the adoption of resolutions supporting the “311” proposal.

The advocates met with the “311” program staff responsible for programmatic and policy changes, and with staff from Department of Building Inspection (DBI), Department of Public Health (DPH) Environmental Health, San Francisco Fire Department (SFFD), the Mayor’s Office, the DPH Tobacco Free Project, the Mayor’s Office of Neighborhood Services, and other interested city departments. The purpose of the meetings was to clarify and obtain support for the proposal, and to identify potential barriers and solutions. The advocates then coordinated and facilitated meetings to draft agreements regarding development, implementation, and develop departmental protocols for the new policy, including ongoing enforcement. The project organized and facilitated trainings for staff of the involved City departments on the history of SROs in San Francisco and new protocols for handling complaints from SRO tenants.

In December 2009, 311 expanded the use of the City’s “311” system to become a resource for SRO tenants. The new system allows SRO tenants to call in complaints from pay phones for free and receive a tracking number for the complaint. 311 operators then route the complaints to the appropriate city department for follow up. Complaintants can use the tracking number to follow up on their complaint for possible escalation. The new 311/SRO system was launched at a well attended press conference in San Francisco’s Mission District.

Phase Two. The second policy required SRO hotels to post information about the “311” complaint system in all SROs. The advocates followed steps similar to the first policy, including:

- Decided on the most appropriate method (amend policy, department rules, etc.) to require the posting;

- Creates an asset map using the Midwest Academy Strategy Chart;

- Developed and implemented an educational campaign;

- Organized and facilitated meetings with Mission SRO Collaborative staff, advocates, community partners and allies to develop language for the posting;

- Developed a model policy proposal;

- Organized meetings with stakeholders;

- Identified and met with potential policymakers willing to sponsor the legislation;

- Lobbies the Board of Supervisors and city policymakers; and

- Obtained resolutions from supporting organizations.

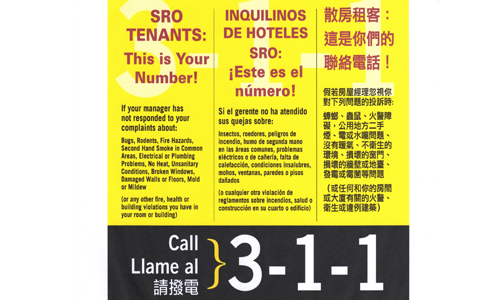

On April , 2010, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors adopted an ordinance requiring residential hotel owners and operators to post a notice advising hotel occupants that they may telephone the City’s Customer Service Center at 311 to report alleged violations of the Housing Code.

5. Enforce and Maintain the Action

On January 26, 2010, San Francisco city officials and low income housing advocates launched the newly expanded “311” system that will benefit the more than 18,000 SRO residents throughout the city. Formerly utilized mainly for outdoor issues (potholes, graffiti, parks, etc.), “311” was expanded to address building issues, such as pests, inadequate heat or water, and blocked fire exits. This was followed by passage of an ordinance requiring residential hotels to post a notice advising SRO tenants about how to use the new resource. The advocates collaborated with Tobacco Free Project and a graphic designer to design the poster and fliers were created explaining the “311” tenant complaint system and required posting.

Following passage of the ordinance, the advocates developed a plan to distribute the signs to SRO managers and fliers to tenants explaining the “311” SRO tenant complaint system and the required posting of the signs. The advocates also planned to organize an educational community meeting for hotel owners, operators, and tenants to explain the new posting requirements.

- CHALLENGES: A major challenge was scheduling meetings with fire, health, and building inspection city staff that were hard to reach because a so much of their time is spent in the community. Coordinating the different city officials and departments that needed to be a part of the project took time, and many follow-up calls and emails. Project staff had to be flexible with meeting times. The Tobacco Free Project, as a part of the San Francisco Public Health Department, helped to facilitate this process by recommending and contacting city officials and other relevant individuals needed to provide input into the project.The advocates were a challenge. All were SRO residents, or were required to have strong SRO ties (e.g. living in shelter but had experience with SROs). Although they wanted to work, many of the advocates also had other issues to deal with, such as emergencies that took them away from working on the project. Some couldn’t afford a telephone, making it difficult to reach them. A great deal of time was spent bringing advocates that missed work up to date. The project coordinator believes that the advocates would have benefited from additional training in the form of “basic building blocks” or foundational work about the project.

- LESSONS LEARNED: It takes a lot of organization to undertake a project of this nature. With the advocates, it took a lot of staying on top of things.

Policy change comes in small increments, and is a major task.

Some initial beliefs about behavior and attitude (e.g. how tenants would prioritize problems in their buildings, what people would say about smoke free buildings) were not accurate. Tenants are afraid of other tenants, including AOD abusers, falling asleep with a lit cigarette and other fire hazards related to smoking. In addition, many SRO tenants have respiratory problems, and “even people who did smoke felt you shouldn’t be able to contaminate the air in common areas.”

This group of advocates was a resource-deprived population and often had emergencies. The project needed to adapt some of the ideas about advocates in the training handbook to better fit the actual population they were working with. Setting limits and being flexible were both important. Some advocates didn’t have access to phones or the internet. Some were non-English speaking, and everyone was living in an SRO or a shelter. To compensate for poor attendance at project meetings, arrangements were made to call advocates without phones on a pay or borrowed phone 30 minutes in advance to remind them about a meeting they needed to attend. Detailed monthly calendars were also printed up in advance so that the advocates knew about important events and meetings. Over time, the advocates learned to use the calendar efficiently. They also became more sociable and gave good report backs about what they learned. - Download: case study

Download the case study here.

Empowering Low Income Residents for Smoking Enforcement (2010)

Dolores St. Community Services

There are more than 19,000 SRO rooms in San Francisco.